by Stephen Vagg

By 1939, the last thing that Ken G Hall of Cinesound Productions wanted to do was produce another comedy. He’d just made five in a row, on top of four others earlier that decade, and was keen to try other sorts of movies – adaptations of Robbery Under Arms and Overland Telegraph, for instance, or films about Melba starring Marjorie Lawrence, or Eureka Stockade (all of which were mooted). But he needed hits in order to stop his corporate overlord, Norman Rydge of the Greater Union Organisation (which owned Cinesound), from shutting down the film division. (Indeed, that might have already happened had not the NSW state government provided a guaranteed overdraft of £15,000.)

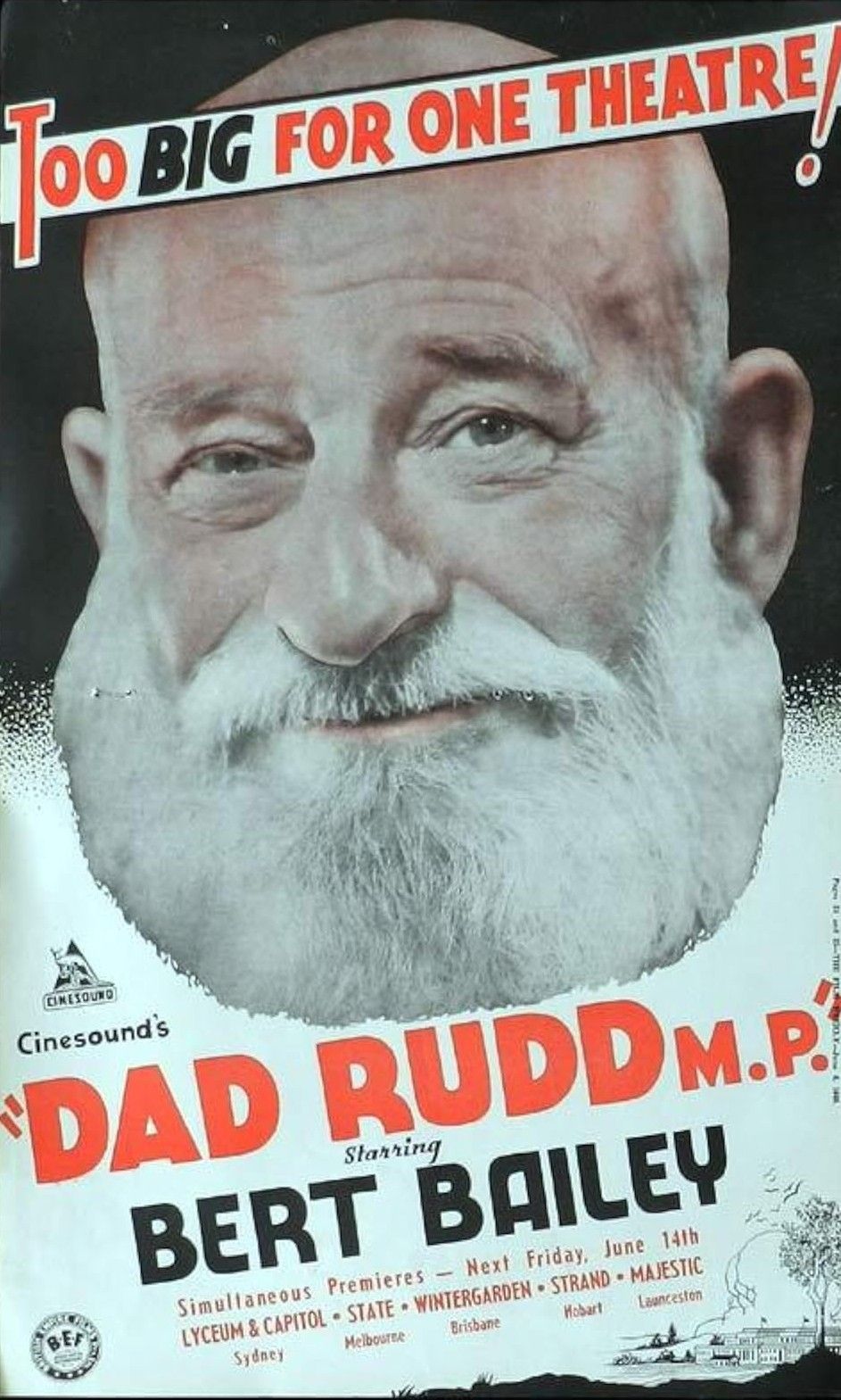

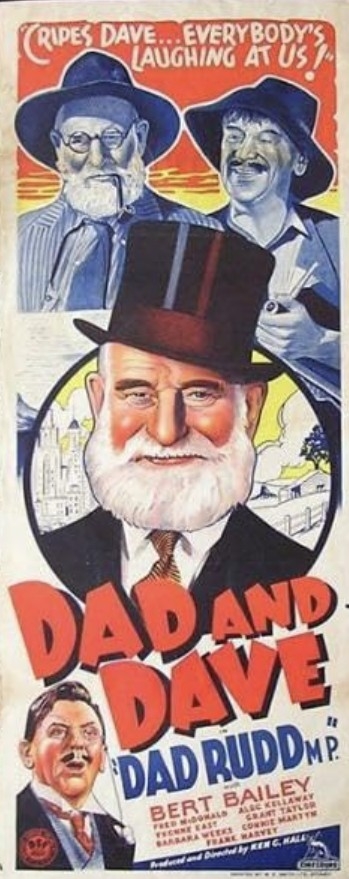

Nothing was more surefire than a Dad and Dave film starring Bert Bailey. There had already been three movies in the series, but the most recent, Dad and Dave Come to Town, had done very well at the box office, so thus begat Dad Rudd MP.

Other topics were floated for Dad Rudd #4 – Dad and Dave in a Haunted House was announced, although Hall probably realised pretty soon that the concept wasn’t strong enough on its own for a feature, and besides, there had been a haunted house sequence in Gone to the Dogs. Instead, he decided to have Dad Rudd run for Parliament – which he’d done in the 1932 film On Our Selection but that was only touched on briefly, whereas here, it’s the bulk of the plot.

Basically, Dad wants the local dam expanded but a wealthy local grazier, Webster, doesn’t, so both men enter as candidates in a local election. Matters are complicated by Webster’s son Jim falling for Rudd’s daughter Ann.

The movie didn’t have too much direct continuity with the first two movies in the franchise, On Our Selection or Grandad Rudd (though Bailey played Dad and Fred MacDonald played Dave in all the movies), but it does flow on directly from Dad and Dave Come to Town. Thus, it reuses much of the cast from that film: Alec Kellaway (returning as the gay floorwalker Entwistle), Marshall Crosby (the neighbour, Ryan) Connie Martyn (mum), Ossie Wenban (Joe), and Valerie Scanlan (Sally) (Peter Finch – who’d been so good as Marshall Crosby’s son in Dad and Dave Come to Town – didn’t come back, unfortunately).

Since Shirley Ann Richards’ character had been partnered off in Come to Town, the role of “hot Rudd daughter” was taken by Yvonne East, a graduate of Cinesound’s Talent School in her first movie. So too was her romantic co-star, Grant Taylor, as well as a whole bunch of attractive females who play models enlisted by Entwistle/Kellaway to help Dad in his campaign (these include the stunning Pat Firman, who later became a television presenter).

The script for Dad Rudd MP was written by Bert Bailey in collaboration with Hall’s regular writer Frank Harvey, who also plays Webster Snr. William Freshman, who had been imported by Cinesound to write and direct Come Up Smiling (the only feature Hall produced which he did not also direct), may have worked on the script – he and Harvey are credited in the copy available online at the National Archive of Australia, but not on screen, which is interesting.

Maybe Freshman didn’t deserve a credit in the end? Or perhaps Bailey’s credit was a contractual obligation/considered better box office? We don’t know, but from our experience of watching these Cinesound movies, it feels as though Bailey would have had a pass at the script, and the structure and romantic scenes of Dad Rudd MP feel very “Frank Harvey like” – it’s a stronger screenplay than Freshman’s Come Up Smiling. Comic sequences were most likely composed by Cinesound’s uncredited gag team.

The main comedy set pieces in Dad Rudd MP included a very funny slapstick fireman sequence (with Chips Rafferty in one of his first roles, unbilled but clearly identifiable), Dad working as a JP with Joe Valli hearing cases from complainants such as Letty Craydon, and Dad explaining the birds and the bees to his son Joe (played by Ossie Wenban who was 45 years old and looks it).

The movie is quite cynical on the Australian political scene – Webster Snr fights dirty, hiring a slimy political operative (played by assistant director Ron Whelan, Cinesound’s resident in-house villain) who does things like hire all the town halls so that Dad can’t speak anywhere, and arranges smear stories and thugs to cause trouble.

The movie is quite cynical on the Australian political scene – Webster Snr fights dirty, hiring a slimy political operative (played by assistant director Ron Whelan, Cinesound’s resident in-house villain) who does things like hire all the town halls so that Dad can’t speak anywhere, and arranges smear stories and thugs to cause trouble.

Dad Rudd MP is more action-orientated than other Rudd movies, with a big climax that involves workers trying to stop a dam from flooding, and these potential voters having to be shifted to the polling booth via flying fox. The latter sequence is probably what got Ken Hall really jazzed about making Dad Rudd MP, as it enabled him to unleash Cinesound’s ace production team including special effects wizard J Alan Kenyon – it’s very well done and makes one sad that they didn’t get a crack at one of those historical epics that Hall had planned, like Robbery Under Arms, Eureka Stockade or Overland Telegraph (the bulk of the team did, however, get to make Smithy, a 1946 biopic financed by Columbia Studios).

The acting in Dad Rudd MP is excellent. By this stage, Bailey and MacDonald had played these roles thousands of times on stage and screen but even at this stage, they never phone it in, and Bailey gets a great bombastic propaganda monologue at the end referring to World War Two.

Frank Harvey is a solid antagonist, Alec Kellaway is terrific as always (as the most sympathetic gay character on Australian screens prior to Don in Number 96), Connie Martyn makes a warm mum, and Yvonne East and Grant Taylor are an attractive and engaging couple. Taylor was a great screen presence, as proved when he appeared in Forty Thousand Horsemen immediately afterwards, although the war robbed him of the movie career that he should have had – as it did for so many others.

Dad Rudd MP performed solidly at the box office though not sensationally and in June 1940 Cinesound announced that it had decided to shut down feature production (which meant Norman Rydge didn’t want to do it).

By then, Cinesound was the one studio in Australia that had cracked the code on how to make consistently successful films – strong production values, emphasis on story, skilful use of stars (genuinely popular comedians or imported Americans who would at least get a lot of publicity) and support players (young ingenues, character actors), and commercial genres. It was a remarkable achievement that has never been matched in Australia, not in films.

The governments of Britain and the US (and Germany and Italy) immediately grasped the importance of cinema in wartime propaganda, but Australia struggled – documentaries were fine, but dramatic features not so much. Cinesound kept putting out films during the war, some of them terrific but they were all shorts, including South West Pacific and 100,000 Cobbers. My “one that got away” was 100,000 Cobbers, which could have easily made a great feature. Dad and Dave dealing with the woman’s army would have also been a terrific idea. These were broad appeal, popular projects that would have reflected the nation’s culture and made money, but they didn’t exist because of the anti-filmmaking culture that dominated Australian institutions at the time.

Norman Rydge wasn’t the only person responsible for the death of Cinesound, but he was head of Greater Union, so the buck stops with him. He could have lobbied the government for its survival during the war, or resumed feature production after the war, or helped filmmakers in countless other ways, but he didn’t. We’re sure that he was a nice guy and everything, but the fact is that the most successful Australian film studio in history was needlessly wiped out at its artistic peak under Rydge’s watch. Australia didn’t get television until 1956 – the market could support local films, especially those made by Ken G Hall and his team. There are many “if onlys” in the history of Australian filmmaking – right up the top is “if only F. Stuart Doyle had remained in charge of Greater Union and not Norman Rydge”. Rydge made a lot of money, though. Good for him.

As swan songs go, Dad Rudd MP is a worthy last feature for Frank Harvey, Bert Bailey and Cinesound’s film department… but it shouldn’t have been a swan song. Cinesound could and should have made at least ten more successful features (something like this: Robbery Under Arms, Overland Telegraph, Eureka Stockade, The Life of Melba, at least three more George Wallace movies, a feature length 100,000 Cobbers and two more war movies). But it never got the chance.

It’s impossible to watch the film (via the National Film and Sound Archive) without a strong feeling of melancholy.