By Colin Fraser

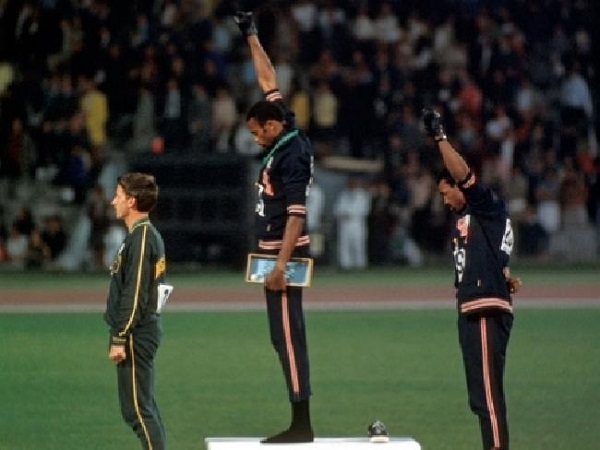

“He’s the skinny white guy in the photograph.” The infamous, now truly iconic shot was taken during the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico. The white guy was Peter Norman, five-time Australian champion sprinter, holder of the Australian 200m record and, for one fleeting hour, the world record.

Peter Norman is the subject of a documentary charting that fateful day in 1968, and the consequences that would hound him for the rest of his life. Largely forgotten except by those who knew Peter well, his filmmaking nephew, Matt Norman, felt that it was time to set the record straight. In short, it was time to give that skinny white guy a name.

Salute premiered at The Sydney Film Festival in 2008 to a packed house. A nervous Matt Norman took to the stage to introduce a film that had been five years in the making. Given the stage microphone, he threatened to sing for his supper, although once the film started, it became clear that he had bigger fish to fry than doing karaoke for festival audiences. Two hours later, Norman received a standing ovation before taking questions from an appreciative and emotional crowd. Again, he offered to sing, but there were no takers. Instead, he discussed his uncle’s turbulent professional life, acknowledging that he would have preferred it if it was Peter on stage instead of him. Sadly, Australia’s best 200m sprinter died in 2006 while mowing his lawn.

For those unfamiliar with the photo, Peter Norman won a silver medal for the men’s 200m sprint at The 1968 Olympics in Mexico. Worldwide, social activism was reaching a crescendo – it was the year that Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were assassinated; Mexican authorities massacred hundreds of students; Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families; and the Australian government maintained a White Australia policy. Flanked by black sprinters, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, Norman mounted the dais wearing a badge in support of The Olympic Project For Human Rights. What he didn’t know was that Smith and Carlos would – with fists raised as the US national anthem faded out in a hushed arena – join in a civil rights salute. One snapshot later, and history was made for the second time that day.

Outraged authorities reprimanded the athletes. Smith and Carlos were sent home, and were suspended by The US Olympic Committee. They later received several death threats. For his part, Norman was reprimanded by the AOC, and was ostracised by the Australian media, who felt that he had shamed his country.

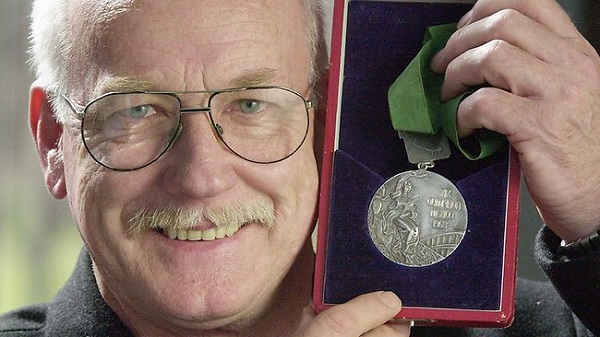

Although he qualified eighteen times to join Australia’s team for The Munich Olympics four years later, Norman wasn’t selected. In fact, he would never represent his country again. To this day, the record that he set for the men’s 200m sprint in Mexico still stands – no Australian athlete has beaten it. Yet when the metaphorical sporting hall of fame was plundered for icons to open The 2000 Olympics in Sydney, Peter Norman was not among them. He was not invited to be a torch-bearer alongside sporting luminaries like Raelene Boyle, a household name who, ironically, won silver for the women’s 200m sprint in Mexico.

Following the Sydney Film Festival premiere of Salute, Matt Norman made his way to Homebush, where The Dalai Lama was greeting admirers, with George Negus and Rove McManus among them. Afterwards, FilmInk spoke to the director on his way to the airport. “I got to meet him,” Norman told us enthusiastically. “It was insane – the whole meeting was held standing up!” It had been a big week for the director, a man whose family’s concern for human rights runs deep. From childhood, Norman recalls that his uncle always steered them along a compassionate path. “I grew up in a hard, hard Victorian country town. We lived opposite an Aboriginal commune, and I was always fighting with Aboriginal kids. I wouldn’t say that I was a racist, but as a child, I had fear of anyone who was different from me. But Peter ran that barrier down quickly – he’d say that we’ve all got our own insights, and our own disappointments. He’d tell me that if you cut a man open – black or white – you’d find the same thing. We’re all the same.”

Some years later, perhaps empowered by his uncle’s perspective, the aspiring filmmaker embarked on a research project that took him to the US for a reunion of the competitors from the 1968 Olympics. Peter Norman went along for the ride. Although he’d been forgotten at home, his actions had earned him a tender place in the hearts of US civil rights campaigners and many fellow athletes. Widely known and fondly regarded, his presence enabled Matt to meet with the American team’s coach, and runners like Lee Evans, Harry Gordon and, most significantly, Tommie Smith and John Carlos. “Tommie and John don’t like each other,” Matt explains. “They don’t even get together for interviews. So when I got Tommie, John and Peter in the same room – and this hadn’t happened for a long time – I realised that I had something special. I had something that was golden.” Tommie Smith and John Carlos would later be pallbearers at Peter Norman’s funeral. Carlos said that Peter deserved to be as well-known as Steve Irwin. “You guys have lost a great soldier. Go and tell your kids the story of Peter Norman,” he told the press on that day.

Salute documents a man who was more than the white guy in the photo. “For the last 37 years, no one knew who Peter was,” Matt Norman says. “They didn’t know that he stood up for human rights, and that he wore the badge on the dais.” Norman devoted his life to his family and sport. He worked for The Victorian Department Of Sports And Athletics. He kept in touch with Tommie Smith and John Carlos, and would do speaking tours in the US. He remained a quietly outspoken supporter of human rights until his death. Without straining the point, Salute managed to choke up a Sydney Film Festival audience of 1,500 cinemagoers. “I always knew that it would affect people,” says Matt. “But I didn’t expect a whole audience to have a tear in their eye.” An emotional crowd gave him a standing ovation that clocked in at five minutes, twenty-four seconds. “Someone timed it,” Norman exclaims. “They rang to tell me. Five minutes, twenty-four seconds. Amazing…”

Decades on, and the rhythm of the world is beating to the same tune, with civil rights abuses rife across the globe. Perhaps learning a bitter lesson from Norman’s experiences, Australian voices are deafening by their absence in Salute. “Peter had a lot of great friends – people like Raelene Boyle – but they didn’t want to talk,” Norman reveals. “They have careers in the media, and I think the last thing that they wanted to do was to put anyone out of place. And all that tells me, despite what Peter achieved, is that we’ve learned nothing.”

Until his death at age 64, Norman was proud to have been a part of civil rights history. “Although he always said that it wasn’t just for civil rights, but for human rights – for people who can’t stand up for themselves.” The US Track and Field Federation proclaimed the date of his funeral, October 9, 2006, to be Peter Norman Day. Tellingly, in Sydney, a mural depicting one of the most significant moments in Australian sporting history – the artwork mural, “Three Proud People”, decorates the side of a house in the Sydney suburb of Macdonaldtown – languishes hidden behind roadside barriers…