by Paris Pompor

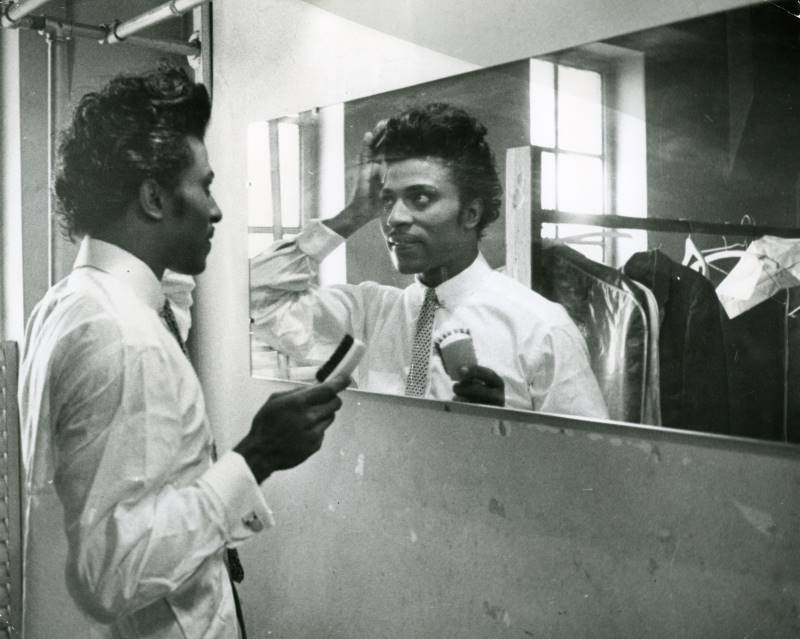

There’s a particularly poignant moment towards the end of director Lisa Cortés’s documentary Little Richard: I Am Everything, when a former band member begins crying at a memory. He is recalling the night in 1997, when Little Richard received the American Music Award of Merit at a gala concert event. “The Architect of Rock and Roll” – as the star born Richard Wayne Penniman became known – was also barely holding it together on the night, as footage of his acceptance speech during the documentary shows.

This wasn’t the first major award Penniman had ever received, but it was the first time he made it to the award ceremony and was able, albeit rather emotionally, to command the full spotlight and claim his dues in front of his music industry peers.

This is a recurring theme throughout the documentary. It taps into not just Penniman’s long-overdue recognition as a musical tower of power, but the music industry’s inherent racism and homophobia; ingrained prejudices that claimed rock ’n’ roll as the domain of a white, western, macho mainstream.

As the originator and inspirational blueprint for everyone from Elvis, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones to James Brown, Little Richard had to continually stake his place in history. He knew that without repeatedly and loudly claiming space, he would be erased. Being the first to do something doesn’t guarantee success or fame, it just makes it easier for others to. Paving the way for pale imitators to have financially lucrative careers doesn’t assure you a place in music’s pantheon either. Like many other groundbreaking Black and Queer artists, Penniman was acutely aware of appropriation and the whitewashing that follows.

While record executives decided a more “palatable” and distinctly beige Pat Boone could take Penniman’s signature tune Tutti Frutti to the top of the charts (which he did, selling bucket loads more than the Little Richard original), it’s safe to say Boone and his suburban bobby-socked fans had no idea the song was all about anal sex. A wop bop a loo bop a lop bom bom indeed!

Songwriter Dorothy LaBostrie, who appears in the documentary decked out magnificently in purple, remembers pitching in to help clean up Penniman’s originally “nasty lyrics.” While follow up Little Richard hits may have toned down the words, his gender fluidity, eyeliner, wigs, sexual gyrations and propensity for ripping off shirts on stage left little doubt what the music was all about. As Little Richard graduated from illicit gay speakeasies and 1950s drag haunts to concert stages around the world, Penniman remained unapologetically queer. That is, until on his way to Sydney for an Australian tour in 1957, he witnessed something supernatural through the aeroplane window. He was convinced angels were holding up the troubled aircraft. Later, on the ground in Sydney, he saw a ball of flame shooting across the sky, unsettling his nerves further. It turned out to just be the Sputnik 1 satellite overhead, but Penniman was convinced it was a sign from god. The fiery message from above? Give up secular music and repent.

And thus began a recurring cycle in the story of Little Richard and an unresolved, ongoing internal conflict. Two warring Pennimans were now battling for control of his soul: one, the loudly proud queer and joyous performer who could hold a rapt audience in the palm of his manicured hands; the other, a god-fearing man of faith who sometimes used interviews to proselytise or call out fellow members of the LGBTQI community who first embraced him.

Little Richard: I Am Everything explores this personal tug-of-war in depth, while also fully celebrating Penniman’s uniqueness, talents and legacy. Employing archival footage, viewers not only see Little Richard in action, but also experience some of the fascinating queer spaces of the 1950s and the LGBTQI+ stories of those who came before him and those he inspired. It’s an especially riveting story if you’re not fully across Little Richard’s career. It’s also nicely edited into a largely linear timeline of his life, although we could have done without some of the film’s oddly sci-fi-esque graphics and image montage segues.

Having passed away in 2020, director Lisa Cortés wasn’t able to interview Penniman himself, but she did manage to talk to Ernestine Harvin, who Penniman was married to for a time after his first religious epiphany. Cortés has also assembled insightful on-screen talking-heads to help flesh-out the story and speak truth to issues of race and sexuality explored in the film.

As always, transgressive mondo trash filmmaker John Waters is entertaining with his anecdotes. From sketchy memories of stealing Little Richard records as a youngster in Baltimore, to his pointed quip that “even racists liked the Black music stations” who played those same records, even if these listeners would have openly championed the segregation that still gripped America. Besides Waters, on-screen interviewees include musicians Nona Hendryx, Mick Jagger, Tom Jones, Nile Rodgers and the wonderfully effervescent and empathetic Billy Porter, who will play James Baldwin in an upcoming biopic. Alongside these are a terrific array of articulate and incisive queer academics, social science historians and trailblazers including Sir Lady Java, Tavia Nyong’o, Zandria Robinson and Fredera Hadley.

Affable director Lisa Cortés joined FilmInk from the US to also talk about Little Richard: I Am Everything, and was genuinely excited that it was premiering in Australia at the Sydney Film Festival in June.

We imagine, for a director, there’s nothing better in terms of gauging how your film is resonating with an audience, than sitting in a theatre watching it with a festival audience. Have you had that opportunity?

This was the opening night film in documentary competition at Sundance this year, so not only was there the joy of having that kind of premiere, but on top of it, people were so happy to be back in person again. I have been able to screen it in a lot of different places, from Oregon to Harlem, Sarasota and Florida. So many different groups of people, multigenerational, and it’s always really moving how people start to interact with the film and also how [when] they leave [they] have a lot of questions for me. People, I think, come with an expectation that it’s a typical cradle to grave story and are kind of struck by how his journey opens one up to explore issues of race, gender, equity… [There’s] the comic side of Richard, the person on talk shows or singing Rubber Ducky or Tutti Frutti, but they don’t understand, I think, how his story is one that is deeply ingrained and connected to greater human struggles.

This was the opening night film in documentary competition at Sundance this year, so not only was there the joy of having that kind of premiere, but on top of it, people were so happy to be back in person again. I have been able to screen it in a lot of different places, from Oregon to Harlem, Sarasota and Florida. So many different groups of people, multigenerational, and it’s always really moving how people start to interact with the film and also how [when] they leave [they] have a lot of questions for me. People, I think, come with an expectation that it’s a typical cradle to grave story and are kind of struck by how his journey opens one up to explore issues of race, gender, equity… [There’s] the comic side of Richard, the person on talk shows or singing Rubber Ducky or Tutti Frutti, but they don’t understand, I think, how his story is one that is deeply ingrained and connected to greater human struggles.

It’s a complex story, and he was a complex man. Even though lots of people appear on screen to discuss him, there’s a sense that you wanted to let Little Richard tell his own story during the film. Is that a fair observation?

Yeah. You tapped into something. In looking at the structure of this story, it was extremely important to me to give him agency, particularly when he was someone who spoke about all that was taken from him. It would not have felt right to allow other people to really narrate the main spine of the film. When we started working on it, I made a concentrated effort to work with the archival team to do a sweep to see if we could find his voice to narrate all the different moments that were important in his life.

Well, you’ve done a fantastic job of that. The archive footage is amazing, especially the photos and footage of queer artists and spaces early on. You must have had quite a research team.

What’s great when starting a project like this is that I was able to do a lot of research just Googling. And then, of course, I read his hilarious book that he wrote with Charles White [Quasar of Rock: The Life and Times of Little Richard]. Once he gave me the breadcrumbs, I then started following, to have a sense of what are the seminal moments and who are the characters who are important to him.

Was there a specific piece of archive footage that took you by surprise or particularly delighted you?

I like the stuff from England. Particularly when he’s performing A Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On! You get such a great sense of how he could wrap an audience around his finger. The beautiful close ups and that black and white footage [with] all the sweat running down his face. How he is relentless in engaging with his audience. And of course, then to have Tony Newman from Sounds Incorporated in the present day talking about that, and then to see young Tony playing backup… all of that. I love that interplay and that conversation between past and present. But always at the front is Little Richard and his dynamic presence. That’s magnetic, that’s cosmic, that’s otherworldly. And how the effect that it’s had on people. Even Mick Jagger speaking about that period is still very much in the present tense. When Mick Jagger is talking about it, it’s not like him going back in time, he is literally at that moment reliving the excitement and magic of [first] meeting Richard.

What was your introduction to Little Richard? Can you remember first seeing or hearing him as a young person and what your reaction was?

I heard him before I saw him. It was summertime, it was dusk, and the fireflies were coming out. A cook-out with the family and all the kids are getting together and singing this song and jumping around and experiencing a lot of joy, not knowing what it was about, but tapping into, I think in some ways, the innovation of what he did with Tutti Frutti.

You’re right, he did provide a lot of joy through his music. And the film tells an affirming story, especially for queer people, but it’s also a sad story because of his struggles and his inability to fully reconcile his sexuality and musical gifts with his religious faith.

Many people have shared that sentiment. What was important for me was to not script how I wanted his life to end, but to be true to his words. And we were almost literally done with… finish[ing] the film when his ex wife Ernestine [Harvin] called and said there were some things that were really important to him that she would love to have the opportunity to share in the film. We had no more money to film her [but] we got a recording done. I really loved her contribution to give us a sense [that] at the end of his life, he was happy in the most important relationship to him, which was with god. Now, would I have wanted him to embrace all that he was and all that he gave? Yes, that would be my intention. But it’s not my story, it’s his.

What would you most like audiences to take away with them or to ponder after seeing the film?

I think so many people come in thinking they know about him and then discover, wait a minute, he did X, Y and Z?! He was an incredible contributor to this genre of rock and roll. He was a mentor to so many greats who followed after him. And he was Black and he was queer. And I think in elevating him and his contributions, we can’t forget that.