By James Hughes

When Risky Business raised its head on free-to-air recently, I parked on the couch expecting something like a large bag of Doritos – fun to consume mindlessly, until self-reproach sets in. Its chances of having improved with age seemed slim.

For anyone unfamiliar with the 1983 movie, Risky Business involves a teenage boy and a prostitute solving a problem by pooling their friends. Put another way, they turn his family home into a thronging brothel.

Before achieving that, they sink his father’s Porsche in a lake, traumatise his mother’s Faberge egg, tangle with Guido the Killer Pimp and have sex on a train.

Hold that scrambled synopsis. And hold your joke about public-transport still being a bit of a grind. Risky Business, as I quickly found, had more than hijinks. What exactly did it have?

Henry James once said of storytelling, keep a dream and lose a reader. First time writer-director Paul Brickman insisted on keeping his and opening with it. Risky Business starts with an erotic dream souring to failure. In that anxiety, there’s instant intimacy. It’s a ruthless viewer who turns away from “I’ve just made a terrible mistake . . . my life is ruined.” Straightaway, we plug in. Straightaway, too, the tones are on the shadowy side. We’ll get to the film’s look; for now, let’s stick with its language.

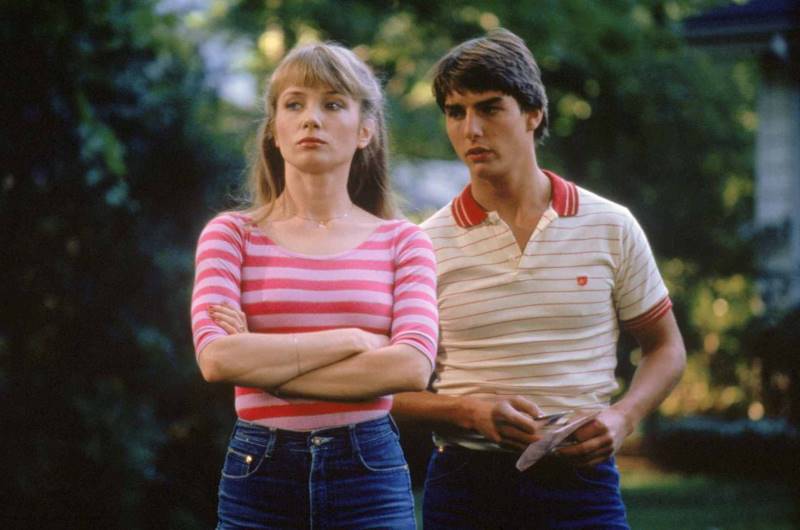

One of the first things that Risky Business had going for it was a thing that its writer had at birth: intelligent wit. (Brickman’s father was a cartoonist at Chicago Tribune and whichever gene enables pithy expression did not skip him.) Take this quiet exchange between Joel (Tom Cruise) and Lana (Rebecca De Mornay) when their enterprise is really rolling:

‘Some of the girls are wearing my mother’s clothing.’

‘So, what’s wrong with that?’

‘I just don’t wanna spend the rest of my life in analysis, could you talk to them.’

Delivered without ham, it’s typical of the movie – it never throws itself at us. It never needs to. There’s not a weak line permitted entry and not a weak link cast. Each player seems physically and aurally made-to-order. This has the rare aggregate effect of making an implausible story feel not just plausible but inevitable.

As Guido, future Soprano Joe Pantoliano drapes an arm around Joel’s shoulder, advising in a tone half avuncular, half threat to murder: “In a sluggish economy, never, ever, fuck with another man’s livelihood.” Curtis Armstrong, as Joel’s genially corrupting sidekick Miles, delivers his teenage-philosopher lines with impish relish. “What the fuck brings freedom? Freedom brings opportunity. Opportunity makes your future.”

It’s a much-loved utterance. It may be a bit shrewd for teen-speech, sure, but as catalyst for misadventure, it’s potent.

Forty years after release, it’s easy to say Risky Business had built-in mass appeal. But in a way, it was made against the grain. In early ‘80s American cinema, adolescents were dismally depicted. There were screwball throwbacks like Animal House and Porky’s and Revenge of the Nerds. Another tendency was to a kind of demoralized delinquency: The Warriors, Bad Boys, Rumble Fish, Class of 1984 and a dozen others.

Teenagers buying the tickets were ready for something savvier. The kids in Rumble Fish talk about their disturbed mother and alcoholic father. The kids in Risky Business talk about imminent riches.

“Make money,” is the hands-down verdict when Joel’s friends chew over life’s purpose: “Make a lot of money.” It’s not unhinged to suggest Risky Business helped pour the concrete for a powerhouse film four years later, Oliver Stone’s Wall Street. In that Icarus for the eighties, go-getter Bud Fox reveres Gordon ‘greed-is-good’ Gekko. “Mr Gekko, I’d like to start by saying I think you’re an incredible genius. I’ve dreamed of one thing and that’s doing business with a man like you.”

In Risky Business, Joel says of Lana” “It was incredible, the way her mind worked, no guilt, no doubts, just this shameless pursuit of material gratification. What a capitalist.”

Both films are about lust for money. Only one is about lust.

The one about lust, if I may, features Rebecca De Mornay. Three-hundred actresses read for the part of Lana, before little-known De Mornay. Casting director Nancy Clopper, having all but concluded that the right actress was not to be found in America, was all set to fly to Paris to continue searching.

The moments building up to Lana’s entrance in the movie are memorably charged; dyed in sensual semi-surreal hues. As Joel dozes on the sofa, evening turns electric mauve through the living-room windows. His bicycle – symbol of his inexperience – tips over in the sighing breeze. It’s as if somebody supernatural is being summoned. When she materialises, in mauve, the sex is pure fantasy.

Joel was meant to be a virgin, wasn’t he? Not bad going on the stairs for a first timer. Hooray for Hollywood’s hallucinations. And for Joel’s study chair. Hooray with gusto for patio doors bursting open and gusts of leaves flying in! Nice. As carnal scenes in eighties entertainment go, Risky Business is in fact mellow. Nobody’s arm is twisted. Nobody’s shoved against a wall.

Interestingly, it’s Joel and Lana’s platonic chemistry that gives the story charm. The friendship rings true. It even feels true when she walks away from Joel in a park, sounding like any other confused young person.

For all its propulsion, for all its twists, Risky Business takes its sweet time. The direction is even pointedly atmospheric. Crafty, lingering shots of everyday suburban acts and stuffs cast a gentle spell: a garden-hose expels a spangled, floating, drooping arc; coils of cigar smoke collude over a card game in a kitchen lit like a wartime bunker; shrivelled leaves skitter in a moonlit driveway. Even a chilled Coke dribbling fizz is new again.

To create the film’s moods and hues, Brickman had a small band of accomplished technicians. Bruce ‘Prince of Darkness’ Surtees had given Dirty Harry its distinctively gritty gloom, with its shadowy faces and bursts of straight-up enamel sunshine. Richard Chew had edited Star Wars.

Unsurprisingly, the making of Risky Business was the business of nuance; of slow-action cuts and short fades to black to join the three-shots to create the illusion of continuous action. Not forgetting optical replica schemes and multiple skip-printing to go from normal motion at twenty-four frames per second to slowing the action to forty-eight – all of that and more just for the train scene.

If sleight of hand makes Risky Business dance in front of our eyes, the performances make it sing. De Mornay brings tints of melancholy and touches of warmth to wily, mercenary Lana. Flashes of candour, ire and gawkiness offset the slinkiness. Then there’s Tom Cruise. Even his most strident detractor would concede that here at least, as a young actor, there was little he could not convey with face, body and speech.

Watch the scene where exasperated Joel repeatedly rings Guido after the house is stripped. And Joe Pantoliano as Guido? Watch the body language the first time he meets Joel. Note the gesture – blink and miss it – at his crotch, his affronted muscle, on “You that kid I chased the other night?” Even the cameos excel. Look at the priceless grimace on Vicki, Lana’s colleague, a moment before she says of the Faberge egg, “Some glass artsy fartsy thing.” Look at the mechanic’s stance, before he deadpans, “Who’s the U-boat commander?”

Intriguingly, after his runaway directorial debut, Brickman turned his back on movie-making.

“I had Hollywood coming at me full throttle,” he told PBS in 2016. “Studio heads were sending me wine goblets and food baskets. People were throwing material at me left and right and lining up to meet me. Some people like that visibility. I had real trouble with it.”

He also had real trouble forgiving a strongarm producer for imposing on the story a more upbeat ending. In Brickman’s initial script, believe it or not, Princeton could not use a guy like Joel. “Very loud,” is how Brickman described that argument with studio kingpin David Geffen. For Brickman, the film wasn’t meant to be about the hero winning. It was about “how American capitalism can warp an ordinary person.” The last line was meant to be “Why does it have to be so hard?”

Safe to say that they got a few things right – three weeks after release, Risky had made four times its cost. Kids were telling other kids. Kids were seeing it twice. By summer’s end, it had netted ten times its $6M budget. Not bad for a script every studio but one had rejected without interest.

So, what happened to Paul Brickman? Six years after absconding from Hollywood, he returned with another screenplay. Men Don’t Leave had the same producer, many of the same key crew returning and a more mature story. It sank without trace and lost millions. Still, it’s a more watchable film than one Brickman turned down after reading a dozen pages and dozing off: Forrest Gump. Less excusably, he turned down Rain Man. Maybe nobody advised Paul Brickman to once in a while say what the fuck?

As Risky turns forty, there’s plenty to like: wardrobe fit for a time-capsule; frictionless gear changes; impelling synthesizer score by Tangerine Dream reserved for the tightest moments. Sound editor Fred Brown warrants mention – and not just because a small sign on his desk displayed two words: Nobody Listens. Listen, as that underwear dance fades, for a distant dog barking, as if endorsing the youth’s unleashed exuberance. Listen for a bell tolling in Joel’s dream, just before Lana walks in. Listen best of all, for a just audible tinkle, when the exultant departing Guido flips the metal tab off his Budweiser to the Goodson’s driveway. “To Joel! Here’s wishing you luck on your future as a businessman coz God knows – you’re gonna need it.”

In forty years, has any flick made getting fleeced, getting in over your head and almost getting fed to the fishes look such fun? Two Hands, maybe? Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels?

Not such a snap then. Not so much Doritos as outstanding nachos.