By Erin Free

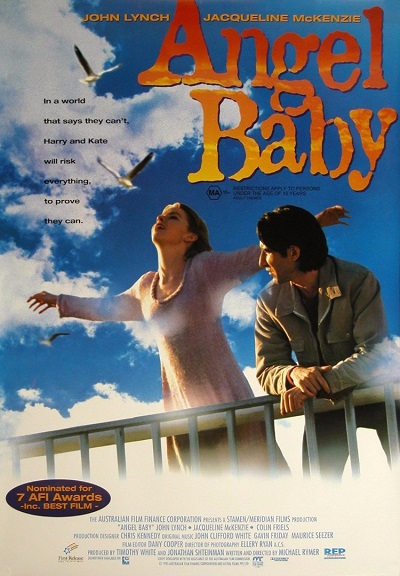

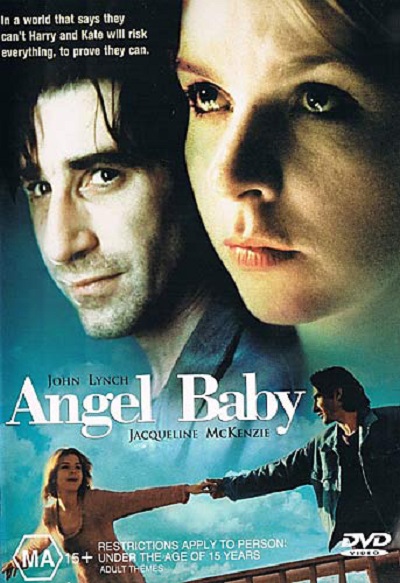

“I poured every ounce of creativity and imagination and energy that I had into Angel Baby,” says writer/director Michael Rymer, talking with obvious fondness and excitement about one of the toughest, most uncompromising films of the nineties. Brave and bold on every possible front, 1995’s Angel Baby tells with lacerating wit and extraordinary sensitivity the love story of Harry (John Lynch) and Kate (Jacqueline McKenzie), two decent but damaged souls buffeted by the horrors of mental illness.

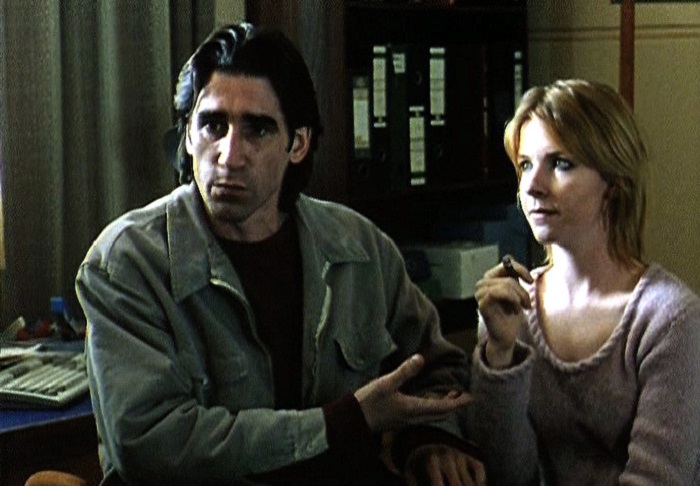

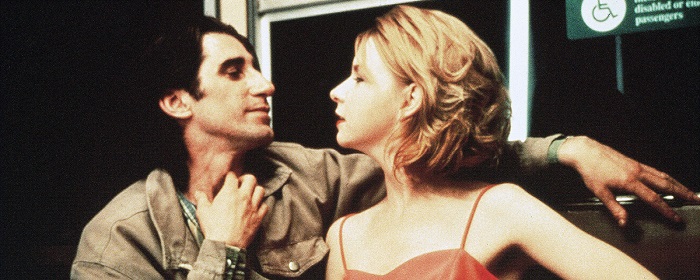

The two meet at a Melbourne drop-in centre nicknamed “The Clubhouse”, where they can find companionship, support and therapy in equal measure. Medicated to fight back the voices in their heads, the pair fall almost instantly in love, much to the surprise and concern of Harry’s supportive and well-meaning brother, Morris (Colin Friels), and his wife, Louise (Deborra-Lee Furness). While the wildly erratic Kate finds life’s answers on the TV quiz show Wheel Of Fortune, the quiet and reserved Harry is slightly more stable, but no less troubled. High on each other, and ecstatic with the news that they are going to have a baby, Harry and Kate make the bold decision to dump their meds. Believing that their love is enough to keep them sane, they soon realise that they are both victims of their own tortured psyches, which will lead them into a world of inescapable hurt.

The script was the second from Michael Rymer, whose first produced screenplay was based upon the notorious Chelmsford case, and resulted in the tawdry 1992 B-grade thriller Dead Sleep, starring Tony Bonner and US import Linda Blair. “I’d written a good little thriller,” Rymer says. “It wasn’t a great piece of writing, but it was a good one. It got made, and it was so badly executed that it was just an embarrassment.” Rymer was determined to make sure that his next script would not receive the same treatment.

Despite Angel Baby’s intense investigation of mental illness, and the manner in which it truly brutalises and forces stigmatisation upon those who suffer it, the film started out somewhere else entirely. “The initial inspiration was nothing to do with mental illness,” Rymer explains. “I have a fairly long standing fascination with the occult and arcane knowledge systems and hidden meanings…the subject matter that The Da Vinci Code basically raped and pillaged. I was ironing out these characters who were very suspicious, and who were always seeing signs and symbols, and it just occurred to me that a lot of people would consider these characters crazy. So I stopped writing and went and studied mental illness, which I knew nothing about. I literally spent six months hanging out in half way houses with schizophrenics. I realised that suddenly I had a plot, and that the illness was the antagonist. It gave the whole love story a lot more structure and urgency. So even though I’m very proud of the authenticity of how we represented mental illness, what I’m most proud of is that the film has a deeper resonance because it’s drawn from imagery and old stories and ancient texts. Essentially, it’s the Mary and Joseph story. I was very, very happy with the script.”

Rymer, however, nearly lost that script. “It’s a long, sordid story,” the director says, obviously not wanting to go into great detail. Rymer had held a reading of the screenplay, which had sparked up considerable interest due to its innate power and slew of fascinating themes and ideas. He ended up optioning the script to someone that he thought was a friend, but who turned out to be exactly the opposite. Rymer found himself bounced off the project, but he was determined not to let Angel Baby turn into another Dead Sleep, and enlisted the help of burgeoning producer Jonathan Shteinman to get it back.

After a minor legal tussle, the project was back in the hands of Michael Rymer, and also Shteinman, who was now officially on board as a producer. In turn, Shteinman (who had worked in a less hands-on capacity on a fistful of previous films) brought fellow producer, Timothy White, into the fold. The considerably more experienced White had a number of major productions under his belt, including The Big Steal, Death In Brunswick, Spotswood and the TV mini-series, Stark. He connected instantly on a deep and very personal level to Angel Baby. “I’d once had a relationship with someone wrestling with schizophrenia, and Michael’s story had echoes of my experiences,” White explains. “Mostly importantly, Michael’s screenplay was not sensational or exploitative. His writing felt like it was coming from an intensely personal place. Jonathan was looking for someone to partner him in producing his first feature. He’d managed to wrestle the rights away from a legal entanglement. We formed a partnership and set about polishing the material. [Playwright and screenwriter] Louis Nowra, who I’d previously worked with on Map Of The Human Heart, was brought in as script editor/consultant for a couple of drafts prior to production.”

When it came to financing, Angel Baby appeared to be in the right place at the right time. The now long defunct Film Finance Corporation was looking to fund four feature films with a budget of 2.5 million dollars each. Described by Rymer as “the chook raffle”, Angel Baby’s gritty story fit within the parameters of the scheme, and the film was essentially up and running. “Every film of this nature has its challenges, but we were hugely supported by Catriona Hughes, the then CEO of The Australian Film Finance Corporation,” says Timothy White, with Michael Rymer firmly in agreement. “It was very well resourced in its day,” the director says. “I swear that I’ve never since then had that much time and money to work with.”

With its strong basis in characterisation and huge potential to be a performance piece of the first order, Angel Baby was always going to be about the cast. Rymer had even studied acting himself for two years in order to better understand the craft, and to give himself the best possible grounding to work with his chosen performers on the film. The day after Angel Baby got the green light, Rymer went straight to his first choice to play Kate. Jacqueline McKenzie had literally torched the screen in the incendiary skinhead drama, Romper Stomper, and had quickly established herself as one of Australia’s finest actresses. She was perfect for the role of Kate, and was offered the part by producer Timothy White, with whom she was working at the time on the TV mini-series, Stark, opposite Ben Elton. McKenzie was so fond of the “wonderful” Timothy White that she was immediately interested when he told her how amazing Rymer’s script was, and when she read it, the deal was officially sealed. “It was so incredibly beautiful,” McKenzie tells FilmInk. “It was finely drawn, moving and sensitive. On Timothy White’s word, it was a no-brainer before I read it, but of course when I read it, I was even more taken with the film.”

The search was then on to find an actor to play Harry. McKenzie was involved in the casting process, and knew who she wanted straight away. “I wanted Richard Roxburgh or David Wenham, but they weren’t fucking available,” she laughs. Rymer then auditioned practically every actor in Australia, and finally thought that he’d found his man. “Michael had prepared tremendously well,” producer Timothy White explains, “but the process was interrupted by the need to recast the role of Harry at a late stage when an Australian actor pulled out because of a commitment to a US film. After exhausting local options, Michael and Jacqueline McKenzie went to the UK with a video camera and tested a number of British actors. It was a very tense time as we were very much geared up to shoot, and we were spending money. We simply didn’t have the resources to shut down and restart at some later point. We would have lost other cast members and probably some of the key crew.”

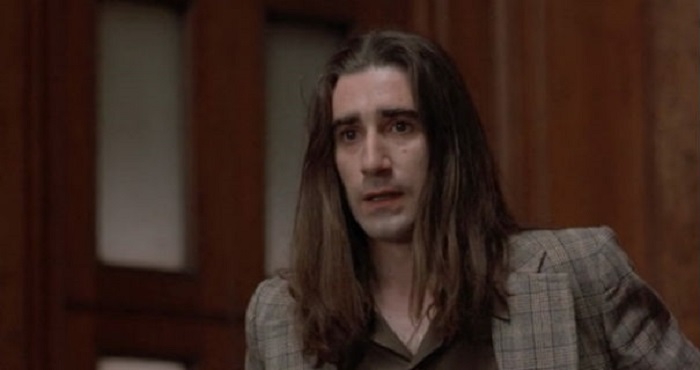

After seeing many actors, McKenzie was most impressed by the appropriately dark and brooding James Frain, who had impressed her in the drama Shadowlands, opposite Anthony Hopkins. “He was amazing,” the actress reveals. “He came in second to last, and he was it, as far as I was concerned.” The auditioning process, however, wasn’t quite over. The last actor to read for the role was Irishman John Lynch, who had made a stunning debut opposite Helen Mirren in the 1984 drama Cal, and was then riding the minor wave caused by his bravura supporting performance in the acclaimed multiple Oscar nominee, In The Name Of The Father. “He’d left his script in the taxi, and he’d lost his bag,” McKenzie says of Lynch’s inauspicious entry into the film. “It was hilarious, but he walked into that hotel suite, and there was no one else that was going to get that role. He was just so special and unique. We just took one look, and we knew; he had this emotional availability which was just essential for Harry. He was a star, and we were really lucky to get him. There is no film without John Lynch.”

Lynch himself was instantly enamored of the screenplay for Angel Baby. “It was brave and honest and challenging, and I don’t look for anything more in a script,” the Irishman tells FilmInk. “I admire any writer or actor who takes on the dark and tries to find beauty there. The film’s themes – of the mind’s fragility, of identity, and of having the courage to love someone when it seems that not only the world but your own illness or self is conspiring against it – really resonated with me.” Michael Rymer was elated to have John Lynch on board. “He’s such a special actor,” the director says. “He’s so authentic and beautiful to look at, but, very much like Jacqui, not in a straightforward, conventional way. I was keen to have someone who could add a certain realism to it. John’s audition was just extraordinary.” Timothy White was similarly impressed…and suddenly considerably more relaxed. “I remember the utter relief when I got a call from Jacqui and Michael saying that they’d found Harry in the form of John Lynch,” the producer laughs. “Jacqui was wild about John’s ability, and I was a big fan from his work in Cal and In The Name Of The Father.”

Lynch was equally impressed, though slightly intrigued, with his novice director. “Michael was quiet, almost painfully so,” the actor offers. “He was very watchful and intense, and he was obviously someone who cared deeply not only about the screenplay that he had written, but about the human condition in general. The filming reflected that; we worked a lot on the veracity of the situations that the characters might find themselves in through improvisation, and through accident, where something none of us expected would come into play and we would go with that.”

The first part of the process for the actors was to engage with the material, and to dig a little deeper into their characters’ complex mental states. Michael Rymer and Timothy White allowed enough time in the schedule for Lynch and McKenzie to do a considerable amount of work on their character’s backgrounds. It was during this period that Lynch really connected with McKenzie as performers. “We were similar, and that was a good place to start from,” the actor offers. “I like to think that we had the same values about acting, and the same emotional courage, to really try and dive deep. We rehearsed a lot for around a week or so, and we connected immediately, through improvising, just talking about the text, and reading it out loud. It was very well cast.”

A major part of Lynch and McKenzie’s preparation involved working with a veteran psychiatric nurse who had years of experience working with patients suffering from schizophrenia. The actors were free to pick his brain on everything that he knew about mental illness, and his experiences in the field. The psychiatric nurse then put them into contact with several invaluable research tools, including hours of video footage and stacks of hospital manuals and text books. “It was amazing,” McKenzie says of the experience.

The nurse then suggested that McKenzie and Lynch return after their research, and that he would interview them in character, allowing them to burrow down even further. “That was an immense, immense help,” McKenzie says. Lynch also valued the experience. “We had a tremendous amount of help, both Jackie and I,” he says. “We also spent a lot of time at a drop-in centre in Melbourne, where we met people who suffered from schizophrenia. We got to see the way that they moved, and what drugs they took and how they affected them…but it was mainly their eyes that intrigued me – that’s where the secrets lay.”

With McKenzie and Lynch fully prepared and geared up to go, Rymer didn’t even have a case of first timer’s nerves when he stepped onto the set. “I’m not good at fear,” he reveals. “I’m not a very fearful person. I remember pulling up with my wife and my sister to the set, and there was a sea of trucks and tents. We just looked at each other and went, ‘Oh my god!’ It had been such a long journey to get to that moment. I had one of those moments where I was like, ‘I could die right now and be happy.’ That’s obviously quite silly, because I wouldn’t have gotten to make a film, but for so long, I’d been thinking, ‘How will I ever get behind the camera?’ So when I finally got there, I was having a great time to the point where I was taken aside by the two exec producers, who said, ‘Michael, you have to look more worried! You’re sending the wrong signals! You can’t be laughing and relaxed.’ But I don’t agree with that. I can get intense, and I know how to move quickly, but for me, it’s more fun than anything. To actually get to do it is mostly pleasure.”

Though the act of finally getting to direct a film was enough of a kick for Rymer in itself, the more experienced members of the team were a little more sensitive to the constant ups and downs of what was essentially a low budget shoot. “It was a tough process,” says Timothy White. “I don’t recall getting much sleep! Like any good director, Michael was determined to find the exactitude that he was searching for. Unfortunately, the ‘search’ usually consumed precious time. We did huge days of overtime that placed a strain on the budget. However, everyone was captivated by the quality of the performances.”

Getting to those truly extraordinary performances, however, was even tougher. According to McKenzie, the temperamental schedule meant that while she and Lynch were often ready to pull the trigger on a major dramatic scene, delays in setting up the shots meant that the pair would often be forced to wait around, with their creative juices subsequently drying up, or exploding violently when they had nowhere to flow. For John Lynch, who was working far away from home, family and loved ones, while also coming to grips with an extraordinarily complex and demanding film role, the on-set delays occasionally became too much.

“It was very emotional material,” Jacqueline McKenzie says. “John is prepared to go to those places that other actors either can’t or won’t, and to get to those places, you have to really open yourself up and be very, very vulnerable. He was absolutely an open wound a lot of the time, and with that comes other stuff – there’s a lot of confusion, and you don’t want to be standing there as an open wound ready with your stuff, and they call you to set and you’re not needed for another half an hour. It’s so tough when you’re in that state, you know? It’s not like we were playing a couple of lawyers bantering their way down the street or something. You’ve basically got your kit and caboodle hanging out, you know? The material was so intense, and it demanded such vulnerability from both of us. On some film sets, actors chuck hissy fits right before a take just to get up to a performance level of energy because they’re too lazy to imagine themselves there. On Angel Baby, the material was so exacting – emotionally and spiritually – that you don’t need hissy fits to get there! We were already there waiting!”

John Lynch concurs: “Yes, it was a tough shoot. Michael was a first time director, and he couldn’t have picked a more difficult subject for himself if he tried. It demanded total commitment not only from him, but also from the cast, every moment of every day. Scenes would change, the content would change, dialogue would be improvised, and rehearsals were very important. When you arrived for work, you had to give yourself to the process and forget about anything else. I love that Jacqueline did that too, but it was tiring none the less.”

The key to the film’s production success seems to be largely down to the presence of experienced producer Timothy White, by all accounts a calming presence with a striking ability to get everybody to focus on the job at hand, and to iron out any wrinkles that threatened to interrupt the complex fabric of the filming process. “We were such a low budget film, and things on set might not have been going to the timetable that we would have liked, and that can always cause issues,” McKenzie admits. “Tim White was so wonderful with that kind of stuff though. He’s very creative, but he’s also such a level headed presence. He had such creative input too. I honestly think that it could have folded at times if it weren’t for him. This isn’t pointing the finger at anyone either; it was just the nature of the material. It was really tough.”

White also seems to have made the experience a less difficult one for Michael Rymer, who ironically appears to have been the one least affected by the momentary jolts of chaos that rocked the production of Angel Baby. “It went very smoothly,” he tells FilmInk. “Tim White was very experienced and cautious and tasteful. I really had no pressure on me like I’ve had since from above; it seems to get a little worse every year. On so many other films and projects, I’ve found myself getting notes and instructions and advice from people who’ve never made films, and you’re sort of going, ‘Really? You think that you’re in a position to say that?’ I listen to everybody’s opinion though; I don’t care if there’s a good idea coming from the caterer – I’ll use it! Studio execs can have good ideas too, but Angel Baby was quite special. I know that now in retrospect because it was exactly the film that I wanted to make. I was sitting in the editing room just quite moved by what we’d been able to do. I had a vision in my head, and the actors then took it ten steps further. The key crew and their creativity came to bear as well, and it was just a wonderful collaboration.”

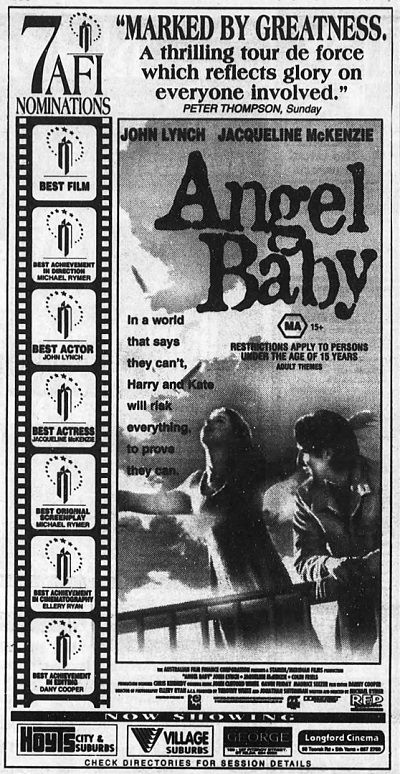

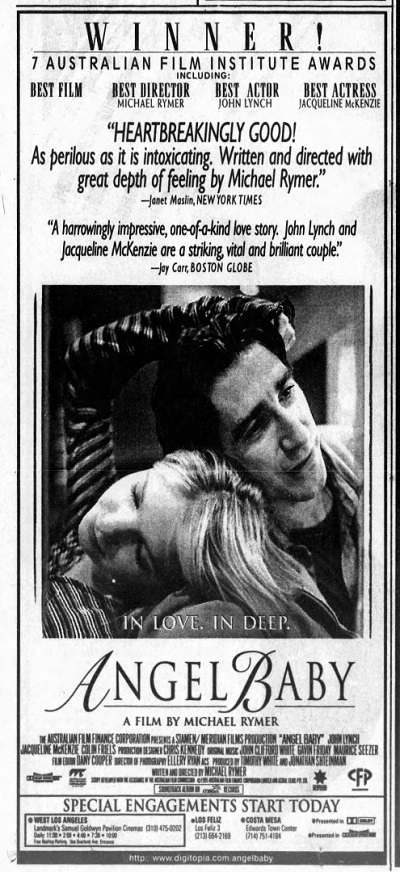

Upon its release, Angel Baby proved an instant success with critics (“This intimate and honest pic, though it undoubtedly will be a tough sell, is a winner,” wrote David Stratton in Variety, pretty much speaking for all who reviewed it), and did solid but far from extraordinary business at the box office. At that year’s AFI Awards (precursors to today’s AACTA Awards ), the film was a major triumph, scoring seven gongs, including Best Film, Best Screenplay, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Actress. “We wanted more people to see the film,” Rymer admits. “It only had a limited release at the cinemas. It got great reviews, and won lots of awards, and that was a wonderful experience to have. The night that we won the seven AFI Awards was really great, particularly being in my home town with my family there. Even the most raving review was saying to the audience though that the film was hard work, and that it would take you through the emotional wringer. It’s very rare that those types of films break out in a big way at the box office.”

For John Lynch, the AFI Award was a quiet joy. “I remember thinking when I received the award that it was going straight on my mother’s mantelpiece,” the actor says. “Every award that I have ever received, I have given to her. On a personal level, of course, your ego goes, ‘Yes!’, and why not, you know? But you can’t live on that stuff…it will kill you. Most importantly, the awards that the film won were a validation of the film itself, and the people involved, from the cast to the director to Tim White onwards.” The AFI Award meant a lot to Jacqueline McKenzie as well. “They always do,” the actress says. “They always have and they always will. Awards like that are important; it means that your stuff is being seen, and if you really care about the material that you’re making, it’s wonderful when it finds an audience. I care about what I make, and I particularly cared about Angel Baby…I really cared about that as a project.”

When FilmInk canvases for final thoughts, everyone seems to view Angel Baby with the same kind of care and fondness that McKenzie did when she was working on it way back in the mid-1990s. “It’s a film that I’m very proud of, and feel strongly connected to,” says Timothy White. “It will live on longer than most of the films that I’ve made. I’ve had the privilege of experiencing it with audiences around the world, and I’ve seen it move them deeply. I’ve also been struck by how many emerging filmmakers recall it with great admiration.”

Though by all accounts the film was occasionally a difficult one for John Lynch, the actor – who has since worked almost non-stop in quality films and high-end television – responds with warmth when asked about Angel Baby. “I’m glad that I did it,” the actor says. “It has become something of a cult film; when people come across it, they really take to it. Peter Howitt, the director of Sliding Doors, saw it and loved it, and gave me a shot at romantic comedy on the back of it, although I would have thought that Angel Baby and rom-com are not very compatible! It gave me the courage to write too; the organic process of the film pushed me in that direction, and I’ve since written two novels [the acclaimed Torn Water and Falling Out Of Heaven], both of which are dark and about the edge of things. Shooting in Melbourne has also really stayed with me. I really enjoyed my time there, and visiting The Twelve Apostles is something that I will remember for a long, long time. I often get people telling me how moving they find the film. It’s a film that I’m very pleased to have been part of…it’s got balls.”

When FilmInk asks the delightful Jacqueline McKenzie where Angel Baby stands on her impressive career resume – which includes quality local films (Beneath Hill 60, Mr. Reliable, Opal Dream), American movies (Deep Blue Sea), and US television (The 4400, Mental) – the actress relates an amusing anecdote. “When I did Hamlet on stage with Geoffrey Rush, Richard Roxburgh and David Wenham, Geoffrey said to me at the time,” McKenzie says, breaking into a pitch perfect impersonation of the actor, “‘Just look around you now, Jacqueline, just look around you. These jobs are one in a million, and when you get to the end of your career, there will be certain jobs that you’ll pinpoint. They are the ones where everything came together, and it was the most amazing experience, my darling.’ That production of Hamlet with Neil Armfield was one of them, and Angel Baby was another. I’ m actually lucky that I’ve got a few of those projects.”

For writer/director Michael Rymer – who has since directed feature films internationally (the locally shot Queen Of The Damned and Face To Face, as well as Allie & Me, In Too Deep and Perfume), as well as working extensively on television programmes such as Battlestar Galactica, Hannibal, American Horror Story, Haunted and the local productions Picnic At Hanging Rock and The Gloaming – Angel Baby was literally the film that started it all. “People bring it up all the time, and gush and say very embarrassingly passionate things,” Rymer says. “I get all uncomfortable…I just get uncomfortable with that kind of praise in general. Angel Baby was the most personal film that I’ve ever made. I love having that as my first directing experience. I was very lucky.”

With very warm thanks and great indebtedness to all who contributed their time for interviews and made this article possible. Angel Baby is currently available on Google Play and other services.

If you liked this story, check out our making-of features on Romper Stomper, Chopper, Praise, Two Hands and Idiot Box.

Great article on one of my favourite films