by Stephen Vagg

Australian audiences have always had a soft spot for stories about a man or woman of God being tempted by the pleasures of the flesh – there was The Thorn Birds of course, the book and miniseries, not to mention “The Priest” segment of Libido, and all those wayward priests in The Devil’s Playground and nuns in Brides of Christ.

Australian audiences have always had a soft spot for stories about a man or woman of God being tempted by the pleasures of the flesh – there was The Thorn Birds of course, the book and miniseries, not to mention “The Priest” segment of Libido, and all those wayward priests in The Devil’s Playground and nuns in Brides of Christ.

This is possibly influenced by the large number of Australian writers who joined the seminary then quit after realising how much they missed, well, sex, including Morris West, Michael Noonan, Thomas Keneally, Tony Scott Veitch, and Tony Abbott.

One of the most popular Australian films of the 1930s concentred on a minister with very strong earthly desires: The Silence of Dean Maitland.

It was based on a play, which was adapted from an 1886 British novel by “Maxwell Reed” (real name Mary Gleed Tuttiett). The novel and its play adaptation were very popular in Australia – so much so, that it had already been filmed in 1914 by Raymond Longford (a very popular movie incidentally, albeit one marked by squabbles between Longford and his producers).

In 1933, Cinesound, Australia’s leading film studio – headed by Stuart F. Doyle and run by producer-director Ken G Hall – was looking for a follow-up to its first two hits, On Our Selection and The Squatter’s Daughter. Both movies had been based on thoroughly road-tested IP, well-known stories that had already worked on the page, stage and screen. Doyle felt that The Silence of Dean Maitland also filled these criteria, so he told Hall that it was to be Cinesound’s next project.

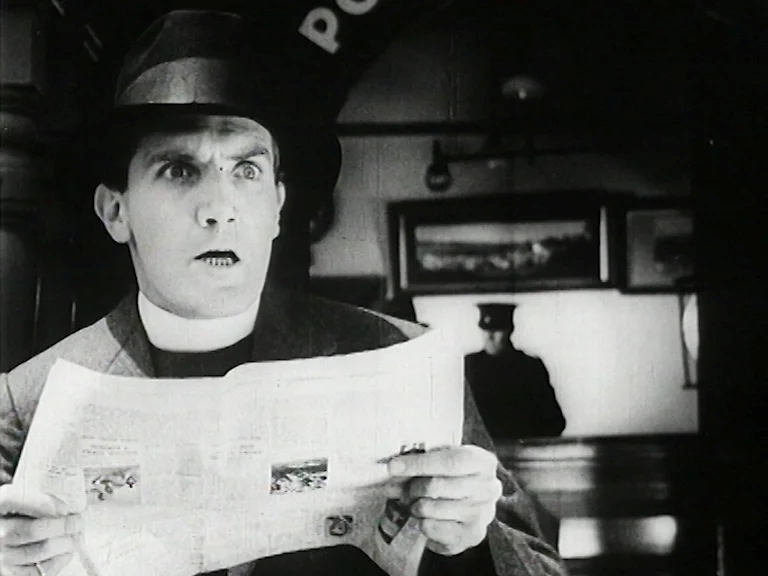

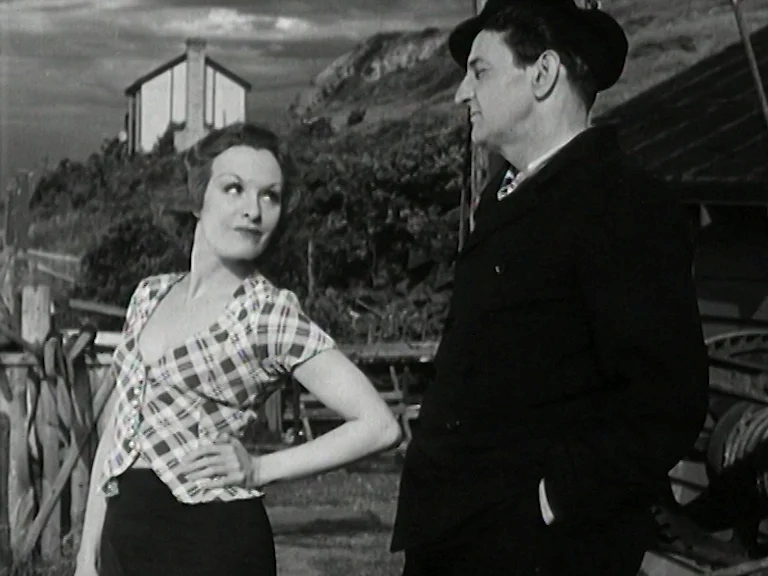

The plot focuses on clergyman Dean Maitland (played by John Longden, an English actor touring Australia) who lives and works in a coastal town. Although engaged to bland, respectable, middle-class Marian (Patricia Minchin), he has an affair with the sexy, working-class Alma (Charlotte Francis), which results in Alma getting pregnant. Alma’s father has a fight with Maitland that results in the former falling off a cliff and dying, but it’s Maitland’s friend Henry (John Warwick) who gets blamed – due in part to Alma claiming that Henry is the father of her unborn baby – and is sent to prison for murder for twenty years. Alma’s love child with Maitland (Jocelyn Howarth) grows up to fall in love with Henry’s son (John Pickard), just as Henry comes out of prison looking for revenge against Maitland, who is a big “star” on the religious circuit.

It’s all solid melodrama, with plenty of plot, sex, God, death and angst – you’ve got forbidden love, illicit sex, illegitimate children, small town hypocrisy, someone wrongly accused and seeking revenge, the next generation suffering for the sins of their parents, etc. Hall also threw in side orders of two ingredients that he liked to add to every movie – some comic relief (there’s some wacky townspeople) and a scene with a girl in a swimsuit (Charlotte Francis does the duty here, getting changed on the beach in quite a racy sequence that Hall cleverly puts at the top of the movie).

At this stage, Hall was still very much in learner director mode, and The Silence of Dean Maitland was technically rough; the pacing is slow, and some of the acting hammy. It’s certainly not as polished as his later movies. However, he was protected by the strength of the story and his cast: John Longden is ideal as the weak tormented reverend, Charlotte Francis is very sexy yet also sympathetic as Alma, while Jocelyn Howarth (from The Squatter’s Daughter) is most engaging.

Location filming helps a lot and it’s solid melodrama; there’s an ending where (SPOILERS) Maitland dies after confessing for his crimes while his blind son – played by none other than Bill Kerr, fifty years before Razborback – sings ‘Abide With Me’… Who can’t enjoy that level of shamelessness? Audiences at the time did – the movie was a big hit, in Australia and England. (Hall thus had three hits in a row, before coming down to Earth with Strike Me Lucky.)

John Pickard, who plays the romantic juvenile, is a wet presence on screen, as so many ‘30s Australian leading men were, but his career turned out fine. Pickard was also a top radio writer, and he emigrated to the US in 1935, quickly becoming very successful cranking out soaps for American radio in partnership with Frank Provo, who was also his romantic partner.

(Random trivia – another gay Australian actor-writer who found success in the US, Sumner Locke Elliot, wrote a stage play, Rusty Bugles, which featured a character who never talked nicknamed “Dean Maitland”, as in “The Silence of Dean Maitland” – that’s how well known the work was at one stage.)

We’ve seen two versions of The Silence of Dean Maitland – one, available at the National Film and Sound Archive, runs for 94 minutes, and another that only goes for an hour. The 94 minute version is, unsurprisingly, much smoother and far more enjoyable – it’s always clear what is going on, which is not the case in the short version.

But the latter is available online

Sex, God, shame, murder, revenge… they should reboot this. The novel’s in the public domain. Just throwing that idea out there.

The author would like to thank Simon Drake and Jodie Boehme of the National Film and Sound Archive and Graham Shirley for their assistance with this article. Unless otherwise specified, all opinions are those of the author.