by Stephen Vagg

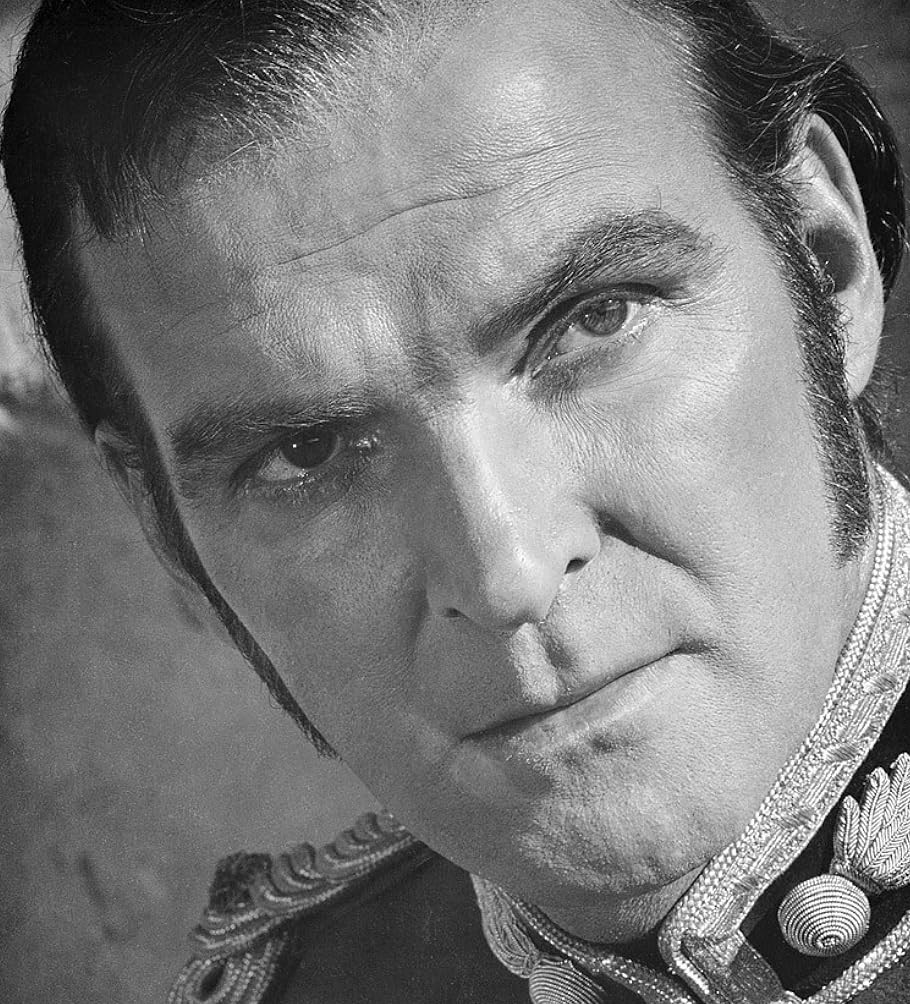

It’s kind of cheating to include Stanley Baker in this series because he was quite a famous actor – not as well remembered as he was, say, back in the 1990s when there was an unofficial law that Zulu (1964) had to be on Australian television every other weekend – but most film buffs would know of him. He was a very busy body behind the scenes as well – mostly to give himself decent roles, it’s true, but not always, and he did try to be a mogul, so he was worth an entry in this series.

Baker was born in Wales in 1928, the son of a coal miner who lost his leg in an accident. Originally more into sport than study, Baker was encouraged to act by local teacher Glynne Morse (being mentored by a teacher is a recurring theme in stories of Welsh actors, eg Emlyn Williams, Richard Burton). This led to school plays, which in turn led to a role in the film Undercover (1943), then an Emlyn Williams play The Druid’s Rest, then a stint in Birmingham Rep.

After his National Service, Baker moved to London where he seemed to be in almost continuous employment straight away, on stage, theatre, radio and television; he was very castable with a great scowly face that was useful for playing sulky soldiers and lurking thugs. Baker was in a stage production of Christopher Fry’s verse play A Sleep of Prisoners that was taken to New York for a brief run. Even more useful career-wise was playing a cowardly sailor in The Cruel Sea (1953) – only a small part but the flashiest one, and the movie was a big hit.

Baker’s career was helped by the fact that Hollywood producers were making so many movies in Britain in the 1950s; Baker was in several, typically as a villain: The Red Beret (1953), Hell Below Zero (1954), Knights of the Round Table (1954), Twist of Fate (1954), Helen of Troy (1955), and Alexander the Great (1956). Baker’s roles in British films started to improve: The Good Die Young (1954), Richard III (1956) (as Henry VII), Jane Eyre (1956) on TV, A Hill in Korea (1956), Checkpoint (1956), Campbell’s Kingdom (1957).

It was an American director in Britain, the blacklisted Cy Endfield, who gave Baker his first real lead in a feature: Child in the House (1956). Endfield went on to use Baker in Hell Drivers (1957), Sea Fury (1958) and Jet Storm (1959). These established Baker as Britain’s leading anti-hero, and first non-comic working class movie star. He would typically play a tough guy, a crook or a cop, who was involved in a heist, either committing it or tracking down the culprits, rather like Humphrey Bogart or John Garfield. The films would be medium budget, in black and white, heavily male focused, gritty and generally downbeat.

In addition to the Endfield movies, Baker was in Violent Playground (1958), Yesterday’s Enemy (1959), Hell is a City (1960), and A Prize of Arms (1962). Another blacklisted American director, Joseph Losey, proved to be an even more amenable collaborator with Baker than Endfield: Blind Date (1959), The Criminal (1960), and Eva (1962). Baker continued to make big Hollywood movies, too, such as The Angry Hills (1959), Guns of Navarone (1961) and Sodom and Gomorrah (1962). And the public did respond – from 1958-62, Baker was consistently voted one of the biggest British stars at the box office.

Yet Baker was hungry for more. He wasn’t a pretty boy, likely to be considered for romance leads – an attempt to change his image, In the French Style (1962), was unenthusiastically received. So, he decided to enter production.

There was a strong tradition of actors turning producer in British theatre, and this had bled a little into the British film industry, notably the movies of Laurence Olivier. Baker was more likely influenced, however, by the success of American stars turned producers such as Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas.

Baker formed a company, Diamond Films, with Cy Endfield and developed a script about the Battle of Rorke’s Drift, Zulu. Finance came from Joe Levine, who’d made Sodom and Gomorrah, which enabled the film to be shot in South Africa. Baker played the lead but brought in Jack Hawkins to co-star and introduced newcomers James Booth and Michael Caine. The movie was a sensation, and Baker was launched as a producer. It remains a remarkable achievement, especially considering Baker had never produced anything before and it was made on location; from all accounts he did extremely well.

Caine wrote in his memoirs that Baker was shocked by the conditions of apartheid South Africa during Zulu, but that didn’t stop Baker from making his next two films there. Dingaka (1965) was an interesting South African court drama on which Baker solely worked as an actor. On Sands of the Kalahari (1965), Baker once more acted and co-produced with director Cy Endfield for Levine. It was an unusual tale – a survivalist story about people who have crashed in the desert – and a tricky shoot; George Peppard walked off the set and was replaced by Stuart Whitman, Endfield clashed with the crew. It flopped at the box office and plans to make other films, like Wilbur Smith’s novel When the Lion Feeds, never eventuated. Baker and Endfield never made a movie together again, although the two men were discussing a prequel to Zulu when Baker died (it became Zulu Dawn).

Endfield’s career never really recovered from Sands of the Kalahari. Neither did Baker’s status as a movie star, oddly enough. He remained in demand but while Michael Caine went into films like The Ipcress File and Alfie, Baker’s roles were underwhelming. He appeared in American television, a UN film Who Has Seen the Wind?, and a change of pace part for Losey with Accident (1967). He never really got a part to match Zulu.

To be fair, by this stage, Baker’s focus was on producing as much as acting. He set up a company, Oakhurst, with Michael Deeley and it made Robbery (1967) a terrific heist movie directed by Peter Yates; Baker played the lead at his scowly best.

Oakhurst made two films without Baker acting: Sleep is Lovely (1968) aka The Other People (1968) and The Italian Job (1969). The former was rarely seen and appears to be a “lost movie”. The second is very widely known – it featured, of course, Michael Caine, who by then had become the huge movie actor that Baker never quite could, due in part because of greater warmth and affability.

Baker produced and starred in Where’s Jack (1969), a film about a highwayman co-starring Tommy Steele for director James Clavell. This was a big flop, and undid much of the good work of Robbery and The Italian Job.

Baker continued to act – The Girl with the Pistol (1968), The Games (1970), The Last Grenade (1970), Perfect Heist (1970) – although none of the movies broke through commercially. Baker was losing his box office allure, which probably hurt his ability to raise finance on movies. He co-produced Colosseum and Juicy Lucy (1970), a concert film, and tried to get up some interesting sounding films, such as an adaptation of George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman, but had no luck.

He bought into Harlech Television, then he and Deeley plus Barry Spikings formed Great Western Enterprises, which became involved in a number of projects (perhaps too many): real estate, pop festivals, buying British Lion. The pop festivals resulted in lawsuits, the stock market crashed, they sold their building to buy British Lion, Baker appears to have been squeezed out of Great Western by Deeley and Spikings. He had to keep acting, and his choices were not ideal: Popsy Pop (1971), A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971), The Butterfly Affair (1972), Innocent Bystander (1972), Zorro (1975).

By now, the British film industry was in freefall. However, television was very strong and Baker started to increasingly work in that medium: The Changeling (1974), Who is Lamb? (1974), Robinson Crusoe (1974), How Green was My Valley (1976).

Baker had so much talent and drive that if he had lived longer, we believe that his career would have re-flourished. It’s not hard to envision him picking up easy money in ‘80s Hollywood with its love for British villains (Steve Berkoff, Alan Rickman) and his love for producing was bound to come up with some first rate projects eventually (in particular, one senses that Zulu Dawn would have been much better had Baker supervised it). But he was a heavy smoker and drinker and died of cancer in 1976, aged just 49; at least he lived long enough to be knighted.

Stanley Baker made an incredible contribution to British cinema, as an actor and a producer. His output as the former was tremendous and culture re-defining – the first real British anti-hero, a symbol of Welsh nationalism, his collaborations with Losey, Val Guest and Endfield, his depictions of cops, his demonstration to Rank that he could play leads just as well if not better than actors like Dirk Bogarde and Anthony Steel, his personification of the fusion of British and American cinema styles. As a producer, he not only made some first rate films (Zulu, Robbery, The Italian Job) and fascinating misfires (Where’s Jack, The Sands of the Kalahari), he was also a notable backer of talent: Zulu launched Michael Caine and James Booth, Robbery led to Peter Yates getting Bullitt.

We’re surprised that after Zulu, Baker never made another Welsh war movie – the story of Owain Glyndŵr, for instance, or the Battle of Kohima. He definitely should have spent more time in Hollywood, where his tough guy image would have fitted in. Maybe he tried, but had no luck.

Still, a remarkable career.