by Stephen Vagg

Years before Red Dog, Bluey or Blinky Bill, there was Chut the Kangaroo in this 1936 film

Australians love their animals (even those who make their living killing them), and it follows that numerous fauna have made an impact on our culture: Bluey, Phar Lap, Skippy, Blinky Bill, Red Dog, Oddball, Horrie the Wog Dog, Dusty, Babe, the Colt from Old Regret, Bob Morrison, Mad Max’s Dog, Razorback, Mumble the penguin, Numunwari the croc, Molly the singing dog (a frequent Mike Walsh Show guest who got her own movie in 1983), the Tasmanian Tiger, the dugong in Long Weekend, the Tassie Devil, various dingoes, Dot’s kangaroo… and Chut the Kangaroo, star of the 1936 Ken G Hall movie, Orphan of the Wilderness.

This film is something of an anomaly in Hall’s oeuvre, which tended to consist of star-driven comedy vehicles, documentaries or melodramas. Technically, Orphan of the Wilderness is a melodrama, since it has a hero who goes through turmoil that would shock a Charles Dickens character, but said hero is a kangaroo, which gives it a very different feel from everything else that Hall did.

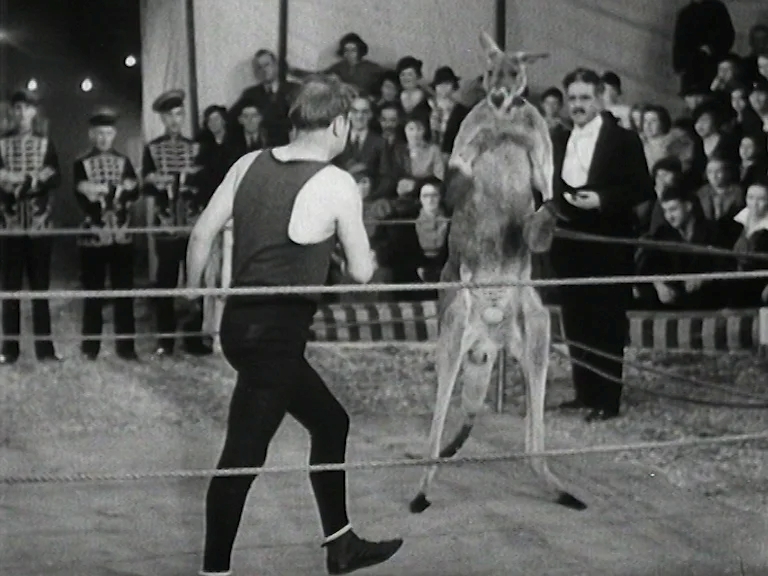

Orphan of the Wilderness starts with Chut as a joey living an idyllic life in the bush until hunters shoot his mother dead. Chut narrowly escapes death himself at the hands of an eagle and a snake, then winds up at a farm run by Tom Henley and his mother. Chut grows up and Tom teaches it to box for “fun” (er… thanks?). An unscrupulous shearer on Tom’s farm starts hosting boxing matches involving Chut; the kangaroo isn’t really into it, so the shearer shoves a lit cigarette into the marsupial’s fur, which makes Chut go berserk, and wound the shearer with his claws. Chut is declared a menace, so in order to save the kangaroo’s life, Tom sells him to McGee, an animal trainer at a circus where Tom’s girlfriend Margot performs (an attempt to return Chut to the wild fails as the ‘roo has become too domesticated). Margot promises to look after Chut, not realising that McGee is a sadist who secretly whips the kangaroo. Chut’s boxing skills make him a star attraction at the circus, but McGee’s constant torture makes the animal snap and turn vicious during a show, causing the crowd to panic. A lynch mob sets out to kill Chut and it’s up to Tom and Margot to save the day, resulting in an all-in brawl between Tom and his friends and McGee and his friends, which the goodies fortunately win.

You don’t see that on Skippy!

Orphan of the Wilderness was based on a story by Dorothy Cottrell, an author who knew something about life’s hardships, having been permanently paralysed after contracting polio as a child. Her book – serialised here – was read by American screenwriter Edmond Seward, who Hall had brought out to Australia to work for Cinesound Productions, and Seward recommended it for filming. The American must have had a thing for animal stories – he also scripted Thoroughbred (1936), based on the life of Phar Lap – though the horse in that film isn’t as front and centre to the narrative as Chut is in Orphan of the Wilderness, which has whole sequences without any humans in them.

The original plan was for Orphan to be a 50-minute supporting feature for Thoroughbred, the way that Hall’s earlier Cinesound Varieties (1934) had been for The Silence of Dean Maitland (1934) – however, somewhere along the way, it was decided that Orphan of the Wilderness should be a proper feature. A possible reason for this may have been the recent box office success of the Clark Gable version of Jack London’s novel Call of the Wild (1935), another movie that focused on an animal.

The original plan was for Orphan to be a 50-minute supporting feature for Thoroughbred, the way that Hall’s earlier Cinesound Varieties (1934) had been for The Silence of Dean Maitland (1934) – however, somewhere along the way, it was decided that Orphan of the Wilderness should be a proper feature. A possible reason for this may have been the recent box office success of the Clark Gable version of Jack London’s novel Call of the Wild (1935), another movie that focused on an animal.

The role of Tom was played by Brian Abbott, a handsome Ronald Coleman type with a newsreader voice and bad teeth. Abbott might have gone on to have a decent career as a radio announcer – we’re not being flippant about that, it was the fate of an earlier Hall leading man, Dick Fair – if he hadn’t been so enthusiastic about sailing. Abbott’s next movie after Orphan of the Wilderness was Mystery Island (1937), shot on Lord Howe Island; when filming finished, Abbott and another actor decided to sail back to Australia in an open boat and were never heard of again. Michael Adams did a six-part series on this for his excellent Forgotten Australia podcast. (Incidentally, Hall’s romantic leading man in Let George Do It, Neil Carlton, was a Brian Abbott look alike.)

Margot was played by Gwen Munro, a lively beauty who should’ve had a bigger film career and was later in Typhoon Treasure and Let George Do It. Her romance with Brian Abbott in this film is quite charming, helped by the fact that she plays a circus performer (a bareback rider) and he’s a farmer – it’s an unusual combination and works nicely. Margot gets to slap one man and whip another, possibly some sort of first for female characters in Australian cinema.

The support cast was, as usual for a Ken Hall movie, very strong. Ron Whelan played a sleazy circus operative, Harry Abdy (one of the best-known animal trainers in Australian showbiz at the time) was McGee, while Joe Valli offered comedy as an incompetent public official. Hall complained in his memoirs about inexperienced human actors slowing down things, specifically excluding Abdy and Munro – we think he might have been referring to Brian Abbott, Ethel Saker (who plays Abbott’s mother) and the various actors playing circus and farm types (there’s a number of kid actors and female circus performers).

Cinesound’s art department really outdid themselves with Orphan of the Wilderness – the movie looks absolutely gorgeous and has a touch of magic about it. There’s a justifiably famous opening sequence of animals in the bush but also Tom’s homey farm, and the atmospheric world of the circus (which Hall sketches with particular vividness). Most of the movie was shot on the sound stage but there’s stunning location footage as well (filmed at Burragarong Valley, the location of today’s Warragamba Dam).

We should note that Orphan of the Wilderness isn’t an easy watch. The kangaroo boxing scenes are quite harrowing, especially as it’s clear that’s a real kangaroo on screen, thumping away. (At least Hall didn’t use a real kangaroo corpse to play Chut’s murdered mother – they drugged a kangaroo and splashed some fake blood on her.) The script really should have had Tom paying no part in Chut’s boxing career, but his character not only trains the animal, he goes to see Chut box under the big top and laughs.

Mind you, the real star of the film is Chut, and that character gets all the sympathy – over the course of 80 minutes, he’s orphaned, kidnapped, repeatedly forced to box by his various owners in front of baying crowds, tortured with a cigarette butt, made to jump through fire, repeatedly bashed in the head, torn away from his girlfriend, deprived of water, regularly whipped, chased by angry mobs, attacked by snakes and birds. It’s an emotionally powerful narrative, leading to a thrilling climax where Tom and Margot have to defend Chut from a lynch mob.

Orphan of the Wilderness is extremely well directed by Ken G Hall at the peak of his powers. We would rank this alongside Dad and Dave Come to Town and Smithy as among the most powerful, moving movies he made. It’s easy enough to view at the National Film and Sound Archive but something this good should be readily available commercially.

The author would like to thank Graham Shirley and the National Film and Sound Archive for their assistance with this article. Unless otherwise specified all opinions are those of the authors.