by Stephen Vagg

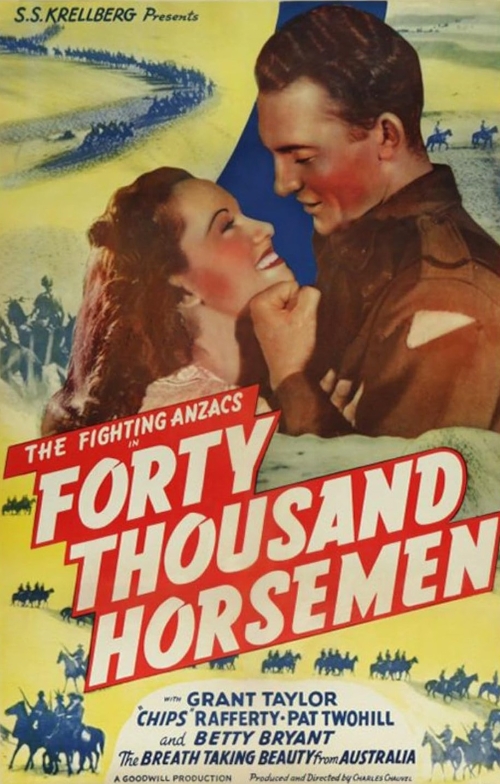

It’s cheating a little to include Forty Thousand Horsemen in a series on forgotten movies because it’s actually quite well known – the 1940 picture was a big hit, in Australia and overseas, and unlike many old Aussies movies has always been relatively easy to see. However, as the years go on and memory of World War One and early Australian cinema fades, we thought that the movie was worth an entry. Besides, we think it’s terrific.

Forty Thousand Horsemen was the sixth feature directed by Charles Chauvel, and the first to make any sort of money – indeed, it was one of the most popular Australian movies made until that date: we have not read any hard and fast data, but in 1946 Chauvel claimed that it cost £30,000 and earned £130,000.

Forty Thousand Horsemen was the sixth feature directed by Charles Chauvel, and the first to make any sort of money – indeed, it was one of the most popular Australian movies made until that date: we have not read any hard and fast data, but in 1946 Chauvel claimed that it cost £30,000 and earned £130,000.

The film centred around soldiers in the Australian Light Horse, mounted troops in the Australian army during World War One, covering their battles in the Middle East and ending with their victory at the Battle of Beersheba in 1917. Chauvel had a family connection with the Light Horse, being the nephew of Lieutenant General Harry Chauvel, who commanded during the campaign.

The Battle of Beersheba was such an Australian military triumph that it is surprising that no film was made about it until the late 1930s, especially considering the numerous movies made about the Battle of the Emden (How We Beat the Emden, The Exploits of the Emden, For Australia). This was likely because of (a) the expense involved in filming a cavalry charge (impossible to do on the cheap) and (b), unlike the Battle of the Emden, Beersheba happened relatively late in the war, by which time audiences were weary of war films, and (c) such was the trauma of World War One, most Australian movies about that conflict during the 1920s and 1930s tended to be downbeat, even the comedies (Fellers, Diggers, Diggers in Blighty).

Raymond Longford had attempted to make a movie about the Light Horse in 1930 called The Desert Legion but was unable to secure finance. Chauvel was also linked to a Light Horse project as early as 1930, which makes sense considering his family connection.

In 1937, it was announced that Chauvel had purchased a Light Horse story from Frank Baker, an Australian actor and stuntman who was brother of famous sports-star-turned-movie-actor Snowy, and who was then living in Hollywood where he was part of director John Ford’s stock company; this story was called For Services Rendered and was going to be done in the style of the recent Hollywood hit Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935) (It’s unclear how much of Baker’s work was in the final movie as he is not credited at all, but Forty Thousand Horsemen does have a Lives of Bengal Lancer vibe).

In 1938, the film’s working title was announced as Thunder Over the Desert. Charles Chauvel raised funds to shoot a “teaser” for the film comprised of a cavalry charge, shot in the extensive sandhills of Kurnell, north of Sydney’s Cronulla Beach in early 1938. This money came from Herc McIntyre, head of Universal Pictures in Australia and one of the true unsung champions of Australian film production, constantly supporting local movie makers over a forty-year career. The results of the teaser were impressive enough for Chauvel to raise the rest of the budget, assisted by £10,000 from Hoyts Theatres (the first time they’d invested in an Australian film) and the New South Wales government guaranteeing an overdraft of £15,000. The movie, eventually titled Forty Thousand Horsemen, began filming in May 1940, several months after Australia had declared war on Germany.

The final script of the movie was credited to Charles Chauvel, his wife (and creative partner) Elsa, and novelist EV Timms. Timms is a forgotten figure today but was a fairly big name in the 1920s and 1930s, best known for his Rafael Sabatini-style historical adventures; he’d previously worked with the Chauvels on Uncivilised. (Timms was also a Gallipoli veteran and was on guard duty at the Cowra POW camp the night the Japanese broke out.) According to an interview that Graham Shirley did with film trade executive Herbert Hayward, the screenplay was given uncredited script editing from Hayward, playwright Sidney Tomholt and film executive Bill Maloney (who was part of Ken G. Hall’s “gag team” of comedy writers for Hall’s movies at Cinesound). Elsa Chauvel, it should be added, insisted to Graham Shirley that the bulk of the work on the script was done by her, Timms and Charles. Regardless of who did what, all the effort paid off: Forty Thousand Horsemen was easily Chauvel’s most accomplished and cohesive screenplay to date. Incidentally, you can read the original script here.

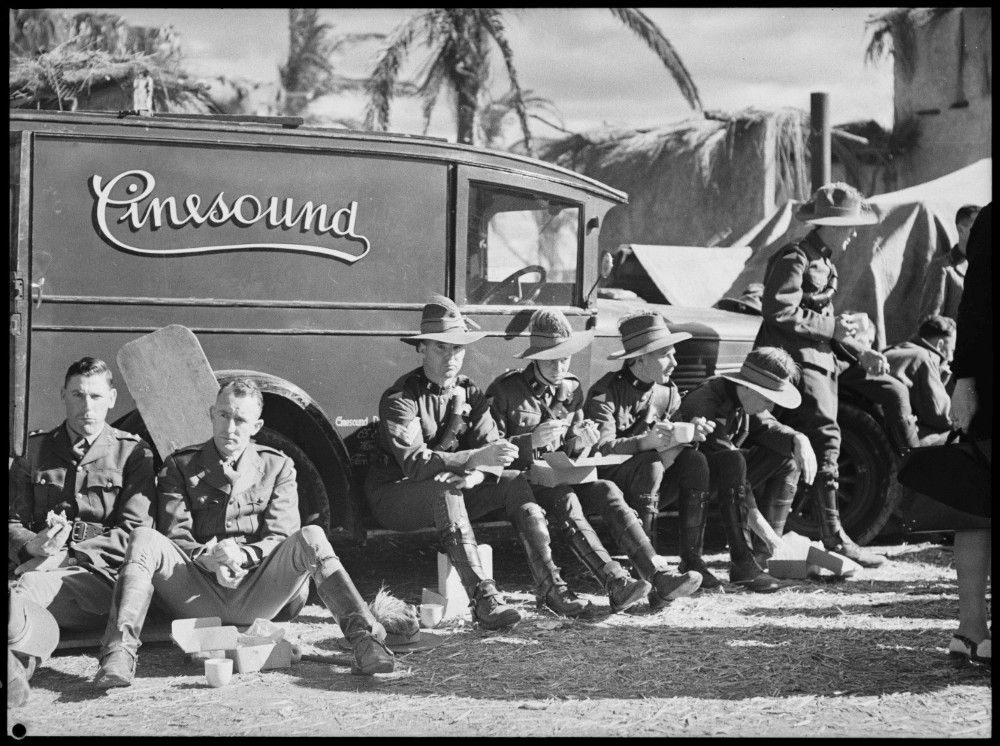

The movie was mostly filmed at Cinesound’s studios at Bondi, with location work done at Kurnell; according to Graham Shirley, there was also second unit footage shot in the countryside near Orange, NSW, and at Broad Meadows, Victoria. The camera crew for Horsemen was something of a “Murderer’s row” of ace Australian cinematographers, including some of the biggest names in our industry: George Heath, Frank Hurley, Damien Parer, Arthur and Tasman Higgins, and John Heyer. The movie was released in late 1940 and, as mentioned, was a huge box office success in Australia and internationally.

We’ll give a recap of the story (major spoilers)…

Forty Thousand Horsemen gets off to a flying start in 1916 Jerusalem, with some evil Germans (led by an over-acting Eric Reiman) knocking over furniture and hanging a Frenchman in front of his daughter (played by newcomer Betty Bryant)… full on! We cut to some Germans and Turks discussing Aussie soldiers – while the German officer makes fun of their feathered hats, the Turkish one speaks up for their courage at Gallipoli (this sympathetic depiction came about because the Turks were neutral during World War Two).

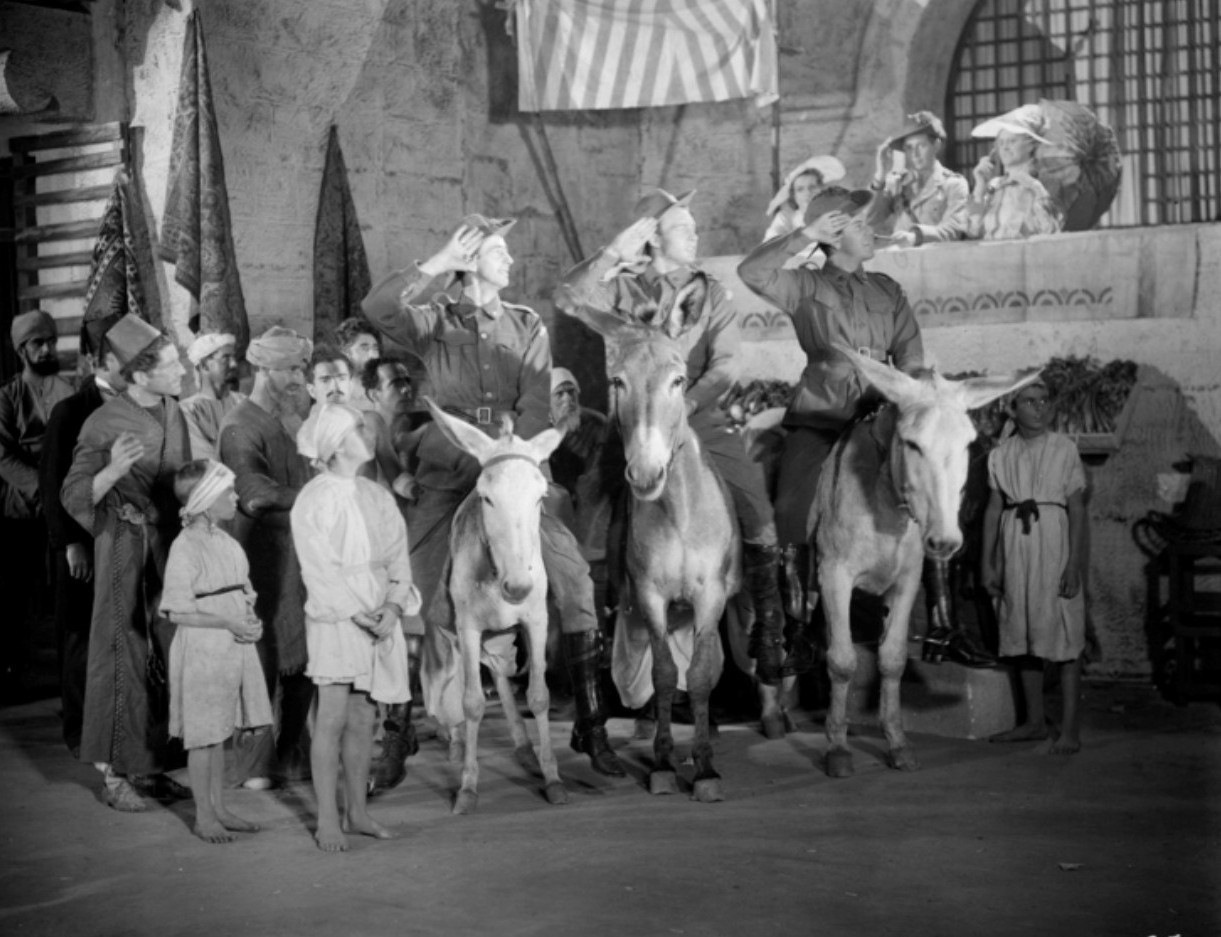

Then we meet the Aussies: three diggers on leave, outsmarting Arab vendors, riding donkeys through the streets, admired by English grand dames and belly dancers. They’re played by Grant Taylor, Chips Rafferty and Pat Twohill; Taylor was a juvenile lead discovered by Cinesound in Dad Rudd MP who became what could be described as an Aussie film star with this movie. He’s good looking, charismatic and masculine, with a terrific physique, relaxed demeanour and confidence, even if his hairline was already receding; Taylor had a fondness for booze and lost his looks relatively rapidly – the cigarettes that he’s constantly puffing on in Horsemen (even while shaving!) probably didn’t help – but he was the most effective Australian “macho sex symbol film star” until Jack Thompson came along (there was Rod Taylor, but he never really got the chance in Australian films).

Chips Rafferty, playing his first sizeable role, had a more notable film career than Taylor, in part because he was more unique – the gangly string bean with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth – and full marks to Chauvel for giving him such a prominent part (especially considering the far more established Pat Hanna wanted to play it); Rafferty’s inexperience is evident, but it’s made up for by his presence – also he has a charming speech about Why We Are Fighting the War. Pat Twohill was a Kiwi, who had extensive stage and later Australian radio experience; he has a nothing part in Horsemen and does nothing much with it. (We always forget that he’s in the movie).

Taylor and Rafferty are singing “Oh, You Beautiful Doll” when the soldiers receive word that the British need their help. “The Tommy’s fight is our fight,” says Taylor, a single line of dialogue which probably added thousands to the film’s box office in Britain. Taylor is then shown traipsing over sandhills on horseback in beautifully-composed shots; eventually, he gets cut off from his men after a battle, but is nursed back to health by Betty Bryant, dressed as a boy and spying on the Germans. She returns Taylor to his regiment, runs into him later on as a boy… then again when she’s dressed as a girl. They start a romance, but he’s called off to fight again.

Another battle takes place – one of the Battles of Gaza – in which both Twohill and Rafferty are killed (this was a surprise) and Taylor is captured and sent to Beersheba. He tries to escape, is captured, then escapes again. He meets up with Bryant and the two of them share a very hot scene in a deserted hut during a rainstorm – both of them wearing nothing but towels and they wind up having sex. No kidding – you don’t see it, but it’s heavily implied, a lot more so than Hollywood films of this era. Taylor eventually leaves Bryant, manages to rejoin his army just prior to the charge at Beersheba – which is spectacular.

It’s easy to see why this movie was such a hit – it’s full of energetic spirits, action and romance, plus beautiful photography and unabashed nationalism: ‘Waltzing Matilda’ plays constantly, everyone loves Australians, Aussie soldiers are depicted as brave, loyal, admired by their enemies and allies and get to have sex with hot French girls, etc, etc.

Bryant is very winning and might’ve had a decent acting career had she not married MGM executive Maurice Silverstein and retired soon after the movie came out. The central story is melodramatic, repetitive and silly but works; you wouldn’t buy it in a World War One movie set on the Western front but the Middle East theatre was where Lawrence of Arabia was running around dressed as an Arab, so it suited more romantic outlandish tales like this one, which has Betty Bryant dressing up as a boy to spy (incidentally, E.V. Timms had written a 1927 book about Lawrence called Lawrence, Prince of Mecca). There are impressive production values – Arab markets, small towns, prison cells, battles over the sand dunes, especially the final charge – and it’s perhaps the most pro-Arab movie made by a white Australian filmmaker.

Forty Thousand Horsemen is a lot of fun, a wonderful demonstration of what our industry could produce with the right team, budget and effort.

You can see a copy of the film on Brollie

The author would like to thank Graham Shirley for his help with this article. Unless otherwise specified, all opinions are those of the author.