by Alireza Hatamvand

It might be disappointing for some film students to realise, while they are struggling to finish the final draft of their first screenplay and trying to gather a crew with the smallest possible budget, that some directors have managed with their debut not only to take a firm personal step forward but also to change the history of cinema forever.

This is exactly what Jim Jarmusch achieved with his ‘almost-debut’ Stranger than Paradise—a film that defined the artistic independent cinema of its time and carries behind it a story that is not only fascinating and worth telling, but also deeply inspiring.

How it was made

Nicholas Ray, the auteur of late classical Hollywood cinema, spent the late 1970s teaching at NYU. Among his students, there was one that he trusted and admired more than anyone else: the young Jim Jarmusch. Ray’s confidence in Jarmusch was so high that he chose him as his personal assistant during the making of Lightning over Water—a documentary about Ray’s own last years, collaborated with Wim Wenders.

Through this project, Wenders also discovered that Jarmusch was a truly gifted young filmmaker. Two years later, after finishing his own film The State of Things, Wenders gave Jarmusch the leftover reels of film stock. What seemed like scraps at the time were turned by Jarmusch into a film that made a strong impression on the cinematic world.

With that film stock, Jim Jarmusch was able to direct his own film – a 30-minute short film called Stranger than Paradise. The film was shown at several European film festivals and received high praise from critics. This success gave Jarmusch the opportunity to turn it into a feature movie, still called Stranger than Paradise, by adding two more parts.

Although this wasn’t Jarmusch’s very first feature—he had already made Permanent Vacation as his senior project in film school, which never received a theatrical release—Stranger than Paradise went on to win the Caméra d’Or for best first feature. It was even named the best film of the year in the U.S. by the National Society of Film Critics, and earned around two million dollars at American art-house theatres—quite impressive compared to its modest $110,000 budget.

The film, itself

Stranger than Paradise has a particular structure, divided into three relatively separate acts. It’s hard to say that it really has a plot—nothing ties these sections together beyond the main characters and the simple flow of time.

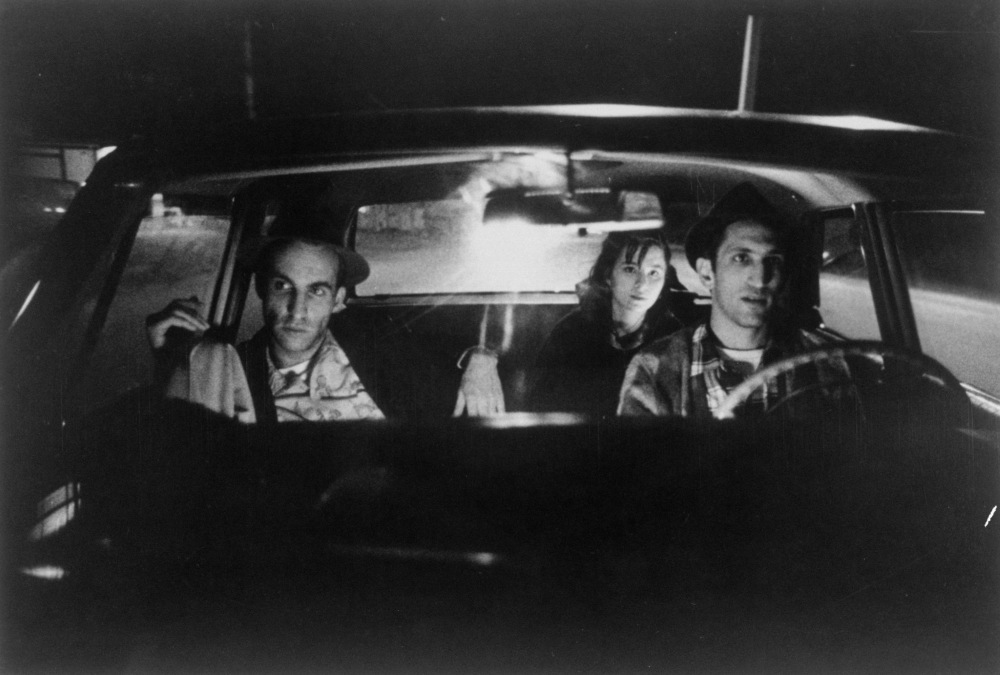

The film follows three people—Eva, Willie, and Eddie (played by Eszter Balint, John Lurie and Richard Edson)—and leans a little more toward Willie than the others. It begins with Eva traveling from Hungary to New York, where she has to spend ten days at her cousin Willie’s apartment. But in Jarmusch’s film, this event doesn’t set off a chain of cause-and-effect drama. In his de-dramatised approach, it’s not classic-written dialogue or decisive actions that shape the film, but rather the empty spaces, the silences, and the seemingly trivial conversations. The mix of ordinary characters and events that never feel larger than life recalls the cinema of Yasujirō Ozu. Jarmusch borrows from the great Japanese director with care, blending that influence with his own New York sensibility.

The acting is deliberately flat and affectless, creating a Brechtian distance that also echoes European cinema of the 1960s—especially another of Jarmusch’s inspirations, Robert Bresson.

Jarmusch made distinct stylistic choices in directing the film. He shot it in black and white—a decision that later became something of a trend in American independent cinema. Each scene is separated by a fade to black, and rarely runs longer than three minutes. Every scene is filmed in a single take with almost no camera movement. There’s no traditional score, which makes the few pieces of music that do appear—like the song Eva listens to—stand out and even contribute to character development.

These techniques not only allowed Jarmusch to make the film on a minimal budget, but also became sources of inspiration. Some filmmakers later adopted them directly; others were simply encouraged by his example to experiment within American cinema. As Jarmusch himself once put it, these were “handmade” films.

How it changed the rules

Spike Lee once said in an interview: “The biggest thing that happened at NYU while I was there was when Stranger than Paradise came out. When that film hit, all of us really believed that we could make it, too. This was one of our classmates—an NYU product.”

Lee wasn’t the only individual encouraged by the film. Its success didn’t remain in New York —it spread across the United States and even the whole world of cinema, becoming a point of reference for young, independent filmmakers everywhere.

The film’s fragmented storytelling and de-dramatised approach stood apart from the glossy Hollywood scripts of the time, showing that a different kind of storytelling could work. Directors like Richard Linklater and Hal Hartley saw freedom in it. Even the three-part structure of Stranger than Paradise became a recurring model in independent cinema. Todd Haynes, for example, made his first feature, Poison, in three distinct segments.

The film’s visual style also left a mark. Long, static shots and minimal camera movement—techniques rarely used in commercial American cinema and more often linked to European directors—suddenly gained fresh relevance. In many ways, the film built a bridge between America and Europe.

What really mattered was the message behind it: you didn’t need a studio budget to make a film that lasts. Something shot on leftover reels, with almost no money and no recognisable faces, could still reach theatres and earn real praise. For young filmmakers, that was a breath of fresh air. It meant that they could give it a shot—and people might actually listen.

Until then, independent cinema often felt cut off from ordinary audiences, as if it only spoke to critics or cinephiles. Stranger than Paradise shifted that. It showed that an art film could still connect with everyday viewers, and in doing so, it helped open American screens to independent voices.

Of course, it’s better to avoid grand titles in cinema. Jarmusch wasn’t the lone saviour or the father of American indie film—that would erase the work of a pioneer like John Cassavetes, who had already paved the way. But Jarmusch did walk into territory that most of his peers either couldn’t see or didn’t dare to explore. And that path is still open, with new generations of filmmakers following it today.

Jim Jarmusch: Less is More, a festival of Jarmusch films, including Stranger than Paradise, is screening at Sydney’s Ritz Cinemas and Melbourne’s Lido and Classic Cinemas from late September