by Stephen Vagg

Over the past century, the flying doctors has been one of Australia’s perennial go-to subjects for dramatists. There’s the current Australian TV series RFDS; a 1985 Australian mini-series (The Flying Doctors) that led to a nine-season series and a one-season spin-off (RFDS); Jon Cleary’s novel Back of Sunset (which was bought for the movies by producer Lawrence Bachmann, though never filmed); a 1959 British TV series (filmed in Britain) created by Michael Noonan which led to a series of popular novels; a long-running BBC radio series called The Flying Doctors mostly written by Rex Rienits, who also wrote a BBC serial on the Royal Flying Doctor Service’s founder, John Flynn, called Flynn; a book biography of Flynn by Ion Idriess called Flynn of the Inland, which was the same title as a proposed fictionalised feature film biopic of Flynn that the McDonagh sisters wanted to make; a long-running Australian comic book Air Hawk and the Flying Doctor which led to a 1981 TV movie. And in 1936, there was the Australian movie The Flying Doctor, a.k.a. the least successful flying doctor tale of them all.

The Flying Doctor is a hard movie to write about because it was such a turkey, and what’s more, a high-profile turkey that needed to be a hit. It was one of a series of movies made following the introduction of a quota in 1935 by Bertram Stevens’ New South Wales government – others include Rangle River and Uncivilised. The Flying Doctor was made by National Productions, a sister company to National Studios who had made Rangle River and constructed a new studio at Pagewood in Sydney.

The Flying Doctor is a hard movie to write about because it was such a turkey, and what’s more, a high-profile turkey that needed to be a hit. It was one of a series of movies made following the introduction of a quota in 1935 by Bertram Stevens’ New South Wales government – others include Rangle River and Uncivilised. The Flying Doctor was made by National Productions, a sister company to National Studios who had made Rangle River and constructed a new studio at Pagewood in Sydney.

National teamed up with the British studio Gaumont-British, then under the control of Michael Balcon (better known for later running Ealing Studios). Gaumont made some really good films in the 1930s, notably early efforts from Alfred Hitchcock such as The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) and The 39 Steps (1935). The studio was always keen to crack the international market, and had enjoyed success doing this with movies such as Rome Express (1932).

In the mid ‘30s, Gaumont decided to make a bunch of movies set in the British Empire, using imported American stars and imperial locations – these included Rhodes of Africa (1936) with Walter Huston (set in South Africa/Zimbabwe), The Great Barrier (1937) with Richard Arlen (set in Canada), and Sanders of the River (1935) and King Solomon’s Mines (1937) with Paul Robeson (set in Africa). The Flying Doctor was Gaumont’s Australian film.

The movie was (according to its credits) “suggested by” a 1934 novel by Australian author Robert Waldron. This concerned a doctor, John Vaughan, who gets dumped by his girlfriend, and runs off to work as a flying doctor in Cloncurry, where he romances a nurse called Ann in amongst all the doctor-ing. We’ve never read this novel, but that sounds like a perfectly simple premise for a movie, with scope for romance, medical drama, life and death plane/outback stuff, and spectacular locations… Like, well, every other drama about the flying doctors ever made.

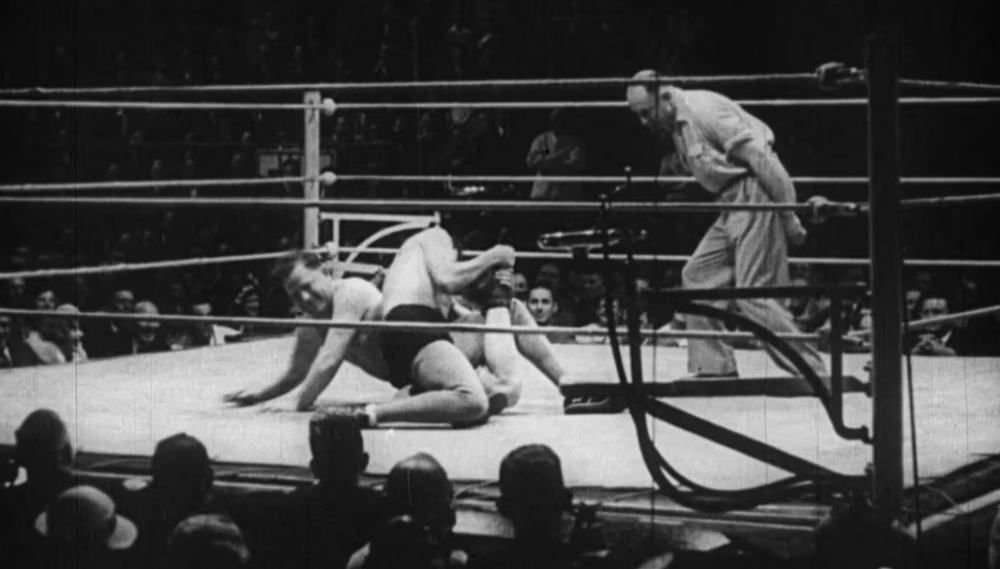

However, somewhere along the line, someone (we’re not sure who, though JOC Orton is credited with the screenplay and Miles Mander directed and is credited with “dialogue”) decided to turn John Vaughan into more of a supporting character. Instead, the 1936 The Flying Doctor is about a guy called Sandy, who we first meet drifting through Australia. He works at a farm, befriends a guy called Dodger, falls for farmer’s daughter Jenny, marries her, abandons her on their wedding day because commitment freaks him out, goes to Sydney, works as a painter on the Harbour Bridge and as a wrestler (!). He is injured in a wrestling match and goes to see a doctor, John Vaughan, who is (a) in love with a married woman, and (b) playing in a Sheffield Shield cricket match against Don Bradman. Indeed, Vaughan bowls to Bradman and dismisses the batter on 99, after which Vaughan is attacked in the crowd by the husband of the married woman Vaughan is in love with, but Sandy intervenes. Sandy gets arrested and goes to prison for a month. Vaughan decides to join the Flying Doctors. Sandy gets out of prison, heads for the outback, reunites with Dodger, and discovers gold. He becomes rich but then loses his eyesight in a barroom brawl, where he is evacuated by the Flying Doctors and is reunited with Vaughan. Sandy discovers Vaughan has fallen in love with Jenny, Sandy’s former bride. Sandy decides to commit suicide, leaving his fortune to the Flying Doctors.

Yes. That is the plot.

A number of British people came out to Australia to make the film, notably director Miles Mander and writer-editor JOC Orton. Orton was a war hero who was head of the script department at Gaumont-British. Mander was an actor-writer director once married to an Indian princess who you might recognise from countless Hollywood films that he appeared in after moving to LA after this film (actually, he moved to LA before filming on The Flying Doctor had finished and Orton took over). Both men have decent credits – Mander’s track record as an actor is far stronger than as director, but he did make the well-regarded The First Born (1928).

(Sidenote: at one stage, Gaumont announced that Robert Flaherty, the noted documentarian, was going to direct a film in Australia, but we gather things got a little tense between studio and director after cost blow outs on Man of Aran (1934), so instead, Flaherty went off to make a film in India for Alex Korda which turned out to be Elephant Boy. We feel that Flaherty would’ve come up with a much better movie than Mander and Michael Balcon probably did too, since the next time he sent a filmmaker out to Australia, he picked a documentarian – Harry Watt – who came up with 1946’s The Overlanders.)

Anyway, back to The Flying Doctor… The role of Sandy was given to American Charles Farrell, who’d been a huge silent era film star due to a series of on-screen romances with Janet Gaynor, notably Seventh Heaven (the duo also had a long affair in real life).

Farrell initially handled the transition to sound quite well but then around 1932 hit a string of flops and by the time The Flying Doctor came around, his career was on the way down. The Flying Doctor didn’t turn things around for the actor, although he later moved successfully into business, becoming a big deal in Palm Springs, having a long affair with William Powell’s wife, which Powell let slide, because Powell was much older than his wife; Farrell later became an alcoholic and died a hermit. [Lucky Stars by Sarah Baker is the book to read on Farrell and Gaynor.]

The part of Jenny, Sandy’s jilted bride, was played by Mary Maguire, who had just been in Charles Chauvel’s Heritage (1935); Maguire later moved to Hollywood, made a few movies, then headed to London, starred in a few more movies, married a rich old dude, presumably thought she was home free, but the old dude was fascist and interned during the war. [If you want to know more, check out Michael Adams’ entertaining biography on the actress, Australia’s Sweetheart.]

Margaret Vyner, who played Vaughan’s married lover, was a model and theatre actress; Vyner moved overseas not long after making The Flying Doctor and married actor-playwright Hugh Williams; they started writing plays together and had some big hits including The Grass is Greener which was filmed in 1960 with Deborah Kerr.

Vyner’s on- screen husband in The Flying Doctor was played by Eric Colman, brother of Hollywood movie star Ronald Colman. James Raglan, who played Vaughan, was a British actor who lived in Australia for a few years appearing in movies like Mr Chedworth Steps Out; he always looked ill on screen.

In other words, there were a lot of interesting people on The Flying Doctor.

This did not result in an interesting film.

The movie is weird. So weird. It feels like a story made up as it goes along, with “stuff” shoved in desperately – ‘Waltzing Matilda’, sheep, cockatoos, the Harbour Bridge, wrestling, cricket, Don Bradman, prison, gold mines, married women, long lost brides, brawls in bars, blindness, nightclubs, planes. Indeed, there’s so much Australiana combined with narrative slackness that at times you’re wondering if the filmmakers are taking the piss.

We can’t understand why Gaumont didn’t make a movie about, you know, a Flying Doctor. Sure, Vaughan is a character, but there’s precious little doctoring in the movie (or flying, come to think of it). If whoever was in power disliked the novel, they should have adapted another novel. Or at least changed the title to something more appropriate, like The Sundowner or something.

Why did they do it this way? Was it to attract Charles Farrell to the role? (Surely, he could’ve played Vaughan?) Did someone think movies about aimless drifters made money? Who was the person (or people) responsible? Orton? Mander? Michael Balcon? The movie cost a reported forty thousand quid – twice what a typical Ken G Hall film cost around this time. National Studios could have made two movies for the price of one, and doubled its chances of striking lucky.

Our own peeve – while it’s great to have movie where one of the leading characters, Vaughan, participates in a Sheffield Shield match against Don Bradman, the filmmakers put up a scorecard showing that it’s a New South Wales versus South Australia game, and list all the players (including names like Bill O’Reilly)… but don’t have Vaughan’s name on it even though he’s bowling. Sloppy.

Some trivia -– the first release print for The Flying Doctor was being flown from Australia to the UK on a flying boat called the ‘Scipio’ which crashed into the sea (irony) off the island of Crete, killing two people on board. The film was retrieved from the ocean, cleaned up, and was released in Britain.

Some more trivia – there are two versions of the movie out there: an Australian cut and a British cut. The British cut is shorter and puts the middle section at the beginning.

Let’s take a walk on the sunny side for a moment with The Flying Doctor – production values are high (as they should be considering the budget), the acting is fine (Farrell is solid, Maguire and Vyner are gorgeous), the photography is lovely, the riffs on 1930s Australian culture are fascinating (flying doctors, Bradman, wrestling, cricket, Harbour Bridge, Lasseter-style gold mines).

But story matters and the film ultimately did poorly at the box office. This failure was important as it encouraged the quota opponents and discouraged Gaumont from investing in further Australian films; Michael Balcon was partial to filming here, and indeed, later at Ealing Studios, greenlit The Overlanders which led to a series of Australian shot movies… if The Flying Doctor had been better made it might have kicked off this cycle earlier, resulting in a bunch more movies and possibly ensured the success of the quota. (NB while in Australia, Orton optioned William Hatfield’s story The Eternal Lure but it was never made.)

Researching the period of the 1935 quota, we feel that perhaps the greatest mistake that the Australian industry made from this time – and this is wisdom in hindsight – was not allying itself more with the British film industry; they could have pushed for a quota for Commonwealth movies, as opposed to just Australian movies. The union of the British and Australian film industries might have been strong enough politically and financially to get such a quota through.

The Flying Doctor. A really stylish fiasco.

Oh, if you want to see the film and you’re in Canberra, it’s screening on 5 October – tickets are here.

The author would like to thank Graham Shirley, Ray Edmondson, and the National Film and Sound Archive for their assistance with this article. Unless otherwise specified, all opinions are those of the author.